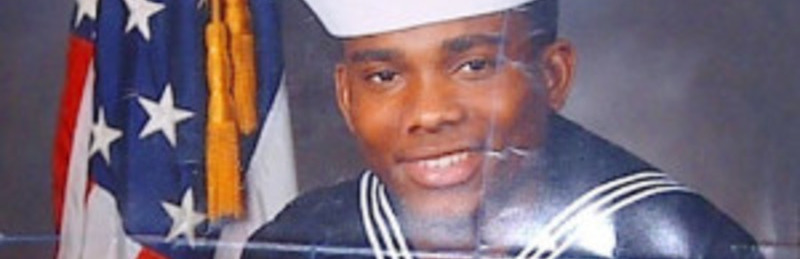

On the morning of his arrest, these were the details of Howard Bailey’s life: He was 40 years old and had been living legally in the United States since he immigrated from Jamaica at 17. He was married and had two teenage children. He lived with his family in a house that he had built in Chesapeake, Virginia. He owned a small trucking business that employed two other drivers. He was a navy veteran who had seen two deployments during Operation Desert Storm. He had not been in any serious trouble with the law since he pled guilty to a marijuana-related offense, a felony, thirteen years earlier.

In short, on the morning of June 10, 2010, everything was fine in the life of Howard Bailey, except that his application to become an American citizen was unresolved after five years. As he tells it, he had no reason to believe that he would not spend another night in this country as a free man.

At six in the morning, Bailey was woken by the sound of knocking. He went downstairs, still dressed in his t-shirt and boxer shorts, and when he opened the door he saw two state troopers. His first thought was that one of his trucks had been in an accident. But that was not the problem. One of the troopers asked whether he had made a citizenship application. “Did you tell them about an arrest in 1995?” he asked. Bailey said he had. That, said the trooper, is why we’re here.

Bailey wondered why the immigration authorities hadn’t just emailed him and asked him to come to their office, considering he had been in touch with them as he tried to resolve his case for years. The troopers told him to turn around so they could handcuff him. He asked if he could go upstairs to put on some clothes. They told him he could not. They advised his wife Judith, who by now had woken up, that she could bring some clothes for him. Then they took him away.

For the next two years, Howard Bailey would be detained in immigration facilities around the country as he tried to halt the deportation proceedings that were unfolding, relentlessly, against him. Finally, in May 2012, he was deported. His wife and children stayed behind.

Bailey told me his story over the phone from Chilani, a town in Jamaica. He had been there for over a year. He had not been able to find a job, so his mother and brothers were helping him with money. His home in Chesapeake had been foreclosed on, and his family was forced to move. His wife, supportive until then, had become angry, blaming Bailey for ruining her life. His children were estranged and struggling. His mother, brothers, uncle, aunts—all the family that he knew—were in America.

It is impossible to know with certainty all the details of Howard Bailey’s life, and at times the Kafkaesque events that led to his deportation strain credulity. But then there is the record, the testimony, hearings, opinions and motions that comprise the government’s case against him, as well as his case to remain in America.

Immigration law is, to put it charitably, a complex set of regulations and decisions about who can stay in this country, and who must leave. The law dictates protocols and procedures designed to determine whether someone is worthy of being permitted to remain. On the morning of June 10, 2010, Howard Bailey stepped out of his home and into a world he thought he understood, only to discover he was wrong.

Is it possible that a man who had faltered in the past, but lived a lawful life for 15 years, could be deported because he applied for citizenship? How did this happen to Howard Bailey?

***

What stood between Howard Bailey and his life in the U.S. was, by his account, a mistake he made in 1995 when he accepted a package for an acquaintance that, it turned out, contained marijuana. He was, he says, clueless about the justice system—he had never been in a courthouse. He says that when he was advised by his lawyer at the time to plead guilty, he didn’t think to ask whether the conviction could affect his immigration status — and neither, he added, did the judge nor his defense attorney mention it. Then he may well have made matters worse for himself when he failed to appear on his court date. In the end, Bailey accepted a plea and spent 15 months in prison.

Now, as authorities sought to deport him because of that conviction, there were on his new lawyer’s reasoning two parallel legal tracks to pursue: one to plead for mercy from an immigration judge; the other to convince a civil court that he had been poorly represented in his criminal proceedings all those years ago.

As it happened, in March 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court decided the case of Jose Padilla, born in Honduras and a veteran of the Vietnam war, who had been living lawfully in the U.S. for over 30 years when he was arrested for transporting marijuana in the course of his work as a commercial truck driver. Padilla accepted a plea bargain after his lawyer told him he “did not have to worry” about the conviction affecting his immigration status.

The court ruled that Padilla’s lawyer had failed his client by offering legal advice that was, in point of fact, not true. Padilla indeed had something “to worry about” – deportation was, as the court put it, a “virtually inevitable” consequence of his conviction, as it is for most drug offenses, except the most minor marijuana crimes.

The court’s ruling meant that Padilla could reopen the criminal case against him. Perhaps Bailey could, too.

Bailey’s original defense attorney, Billy Robinson, had been a high profile and colorful character in Virginia. A graduate of Harvard Law School, he was the first black lawyer in that state’s attorney general’s office. He later served 20 years in the state assembly. Robinson continued to represent clients but often used legislative privilege to postpone court cases—creating long delays that critics argued were unfair to clients and crime victims.

Bailey’s new lawyer, William McKee, was prepared to argue that Bailey had been poorly served.

Bailey had been in immigration detention for six months when his case came before Judge H. Thomas Padrick, Jr. of the Virginia Beach Circuit Court. Padrick was not unsympathetic to Bailey’s plight. “It doesn’t seem fair,” he said of the deportation proceedings against Bailey, “if you’re in the military.”

But Padrick was no fan of the Supreme Court’s Padilla decision. “I guess—I don’t know how this would work, to be honest with you,” he said. “Sometimes the Supreme Court, they just—they are the Supreme Court; but how do you undo something that happened so many years ago? I don’t know.” And then there was the high regard in which he held Billy Robinson – “if I was ever in trouble, I would hire him” —who had died four years earlier, and would not be able to corroborate Bailey’s version of events.

“Well, the defendant would be around to testify as to what was told to him and what he did,” William M. McKee, Bailey’s lawyer, countered.

“That doesn’t seem fair,” Padrick said.

And there the matter stalled, not because the judge didn’t believe Bailey – although he seemed dubious – but because the state supreme court had taken it upon itself to consider how the Padilla case should apply in Virginia. All parties agreed that Padrick’s ruling should await that decision.

Perhaps the immigration court would bring some relief.

Three months later, in February of 2011, Bailey came before immigration judge Lawrence O. Burman in Arlington. McKee floated the idea that the court might take into account the fate of Bailey’s family, his wife and children who relied on him for support.

The problem, however, was the drug conviction.

“Well, unfortunately,” said Burman, “with the aggravated felony drug conviction, there’s not much that can be done. It doesn’t matter what family he has, unfortunately.”

***

For the purposes of immigration law, the term “aggravated felony” originally referred to murder, federal drug trafficking and illicit trafficking of certain firearms and destructive devices. But in 1996, the Immigration Control and Financial Responsibility Act greatly expanded the definition, and removed, in the case of aggravated felonies, the discretion of immigration judges to provide relief from deportation where the circumstances warranted it.

Proponents of the legislation said that the changes were needed because immigrants who had committed serious crimes were not being deported, and undeserving cases were clogging the immigration courts. But it quickly became apparent that people whose cases merited relief were being swept up in the law’s inflexible scope.

“That’s the way a lot of law is made,” Bill McCollum told me. McCollum, a U.S. Congressman representing Florida from 1981 to 2001, was a key supporter of the original legislation, but later attempted to modify some of its toughest provisions. “Something is too loose, too broad. But it’s like a pendulum, it’s way up to the right, and instead of swinging down to balance, even steven with six, you swing the pendulum way out of balance the other way. That’s what happened, in my opinion, with this law.”

One of the most visible and vocal critics of the 1996 legislation was the late New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis, who took special aim at the law in his column. The law’s sponsors, he wrote, had covered up “dozens of provisions to harass and torment legal immigrants” by “disguising it as a crackdown on illegal immigrants.”

Lewis’s anger extended to the sponsor of the legislation, Texas Republican Lamar Smith. In a column titled “Mr. Smith Tells a Tale,” Lewis called a letter that Smith wrote to the paper objecting to Lewis’s critique of the law a “masterpiece of inexactitude.” In a December 1997 interview with Lewis, Smith admitted that a case with similarities to Bailey’s “obviously tugs at your heart” and said, referring to the Immigration and Naturalization Service, that “perhaps around the far edges the INS should have some discretion.”

Smith would go a step further. In 1999, he (along with 27 other members of Congress) signed a letter to Attorney General Janet Reno and INS Commissioner Doris M. Meissner criticizing the INS’s pursuit of deportation in cases of “apparent extreme hardship,” and urging the INS to use “prosecutorial discretion” in starting and terminating removal proceedings.

The reasoning in Smith’s letter was directed at the INS – essentially asking them to show some restraint and subtlety in deciding which cases to pursue most aggressively. But that was up to the INS, not the courts.

Immigration Judge Burman may have been sympathetic to Bailey’s plight. But Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the division that was the successor to the INS in these matters, was not.

Bailey says that during his detention, his lawyer submitted a request that prosecutorial discretion be exercised in his case. His story had many of the elements—military service, family ties in the U.S., and others— that John Morton, director of ICE, had said were relevant to the decision to refrain from prosecution. Bailey says that the request was submitted on a Thursday, but by the following Monday, had been denied.

***

It was clear that immigration authorities declined to exercise their discretion to spare Bailey on at least one occasion. I wondered if there was a second.

When Bailey applied for U.S. citizenship, he disclosed his marijuana conviction, which rendered him deportable, on the application. It appears that the immigration officials who considered his application referred his case to their colleagues in ICE responsible for deportations.

Was that referral the inevitable result of his citizenship bid, or could Citizenship and Immigration Services have denied his request for naturalization without recommending him for deportation?

CIS makes a copy of its policy manual available online. It says that only a person of “good moral character” is eligible for citizenship, and that certain bars to good moral character “may warrant a recommendation that the applicant be placed in removal proceedings.” It goes on to say that this depends on “various specific factors to each case,” and not all applicants who are found to lack good moral character are removable.

The division’s Guide to Naturalization notes that “habitual drunkenness,” for example, might demonstrate a lack of good moral character. It is easy to imagine that such a shortcoming would not lead to a deportation recommendation. By contrast, in Bailey’s case, citizenship was denied because of a criminal conviction that gave immigration authorities the legal right to deport him. Could CIS officers have nonetheless decided, based on an assessment of Bailey’s character and the life that he had built in the U.S., not to recommend removal proceedings?

I posed this question to Joanne Ferreira, a spokesperson for CIS. She advised that she could not answer or speculate, because each case is different and the decisions are made based on various factors.

***

When Bailey appeared in Burman’s immigration court, the judge made an observation.

“It’s never seemed quite right to me that someone with a 10 year old case is suddenly brought into court,” he said. “But on the other hand, he probably should have been brought into court at the time he was convicted.”

This, in the end, may constitute the greatest injustice in Bailey’s case. If he did not deserve to resume his life in the U.S. after he completed his prison term for the marijuana conviction, why wasn’t he deported immediately upon his release? Why was he allowed to spend 13 years building a life in this country under the misapprehension that he could stay?

The government screens inmates in federal, state and local prisons and jails throughout the country to identify non-citizens with criminal records who pose a threat to public safety. Those inmates are deported at the end of their sentences.

It is unclear whether Virginia’s inmates were being screened when Bailey was imprisoned. Around that time, Lamar Smith told Anthony Lewis that the government “has a program to deport those currently in prison when they finish their sentences, but it is deporting less than 50 percent.” That percentage has increased over the years. But advocates for immigrants complain about a lack of disclosure regarding the details of the program, and say that there is little evidence of a standardized procedure for assessing the public safety risk posed by an inmate.

“I was never a threat to society or any person or any thing whatsoever,” Howard Bailey tells me. “I just lived my life and paid taxes and enjoying being American.”

***

When the Virginia Supreme Court handed down its decision on the circumstances in which Padilla-style relief would be available to immigrants in the state, the news was not good for Howard Bailey. The effect of the court’s decision was that a claim of inadequate legal advice had to be filed within two years of conviction, and while the defendant was still in custody.

Supporters of the ruling said that it would ensure that the immigration consequences of old convictions would be considered in the appropriate forum: immigration court. But Mary Holper, then immigration clinic director at the Roger Williams University School of Law, explained to The Washington Post that there was a fundamental error in this logic: “Once someone has an aggravated felony conviction,” Hoper said, “there’s no ‘dealing with it’ in deportation proceedings. It means mandatory deportation.”

Howard Bailey’s lawyer had contemplated one last grasp at staying.

“The only other possible avenue that I can think of right now is possibly a pardon from the governor,” McKee said to Judge Burman in Bailey’s February 2011 immigration hearing.

“Well,” Burman replied, “that’s probably even less likely than a vacation at this point.”

Bailey says he never appeared before a judge without hearing something similar. “They all said: Nobody can do nothing,” he says. “That’s the story of my life. A penny short and a day late.”

And so, Howard Bailey really had no other avenue at all. In May 2012, he was sent to Jamaica, a country he hadn’t seen in 21 years.

He says that it has been difficult to adjust—that he never imagined how hard it would be, just to survive. “Financially, emotionally, just looking out for your own safety,” he says. “It’s a challenge every day.”

He tries to blend in, but small things—his accent, the way he carries himself—betray him. “Everybody wants to go to the U.S.A.,” he says. “So when somebody comes back, they consider you a nobody.”

But worst of all, says Bailey, is the feeling that he has let his family down. He is desperate for his children to understand that he did not leave them intentionally. “I’d rather die than feel this pain,” he says.

Bailey tells me that he has bought some pigs and chicken, and that he is going to try to make a living by raising and selling them. But he says that feed is expensive, so he doesn’t know if the exercise will be profitable.

His days as the owner of a small American business seem like another lifetime, now. The trucking company, called Dutch B’s, shared the name that Bailey had adopted as a Caribbean

and Reggae music DJ on local radio stations in Virginia. It was one of a grab-bag of jobs—in construction, as a chef’s helper, loading ice—that he worked, often two or three at a time, as he kept the promise he made to Judith back in 1997, when she would strap their infant son into a car seat and drive their little Toyota with no air conditioning through the 95-degree heat to visit him in prison: I will do everything in my power to make sure you never have to go through this again.

***

In 2011, a Boston man faced deportation to Kenya after a drunken-driving arrest. The Boston Globe reported that the man told the police who detained him, “I think I will call the White House.”

It turned out that Onyango Obama, known as Omar, was the half brother of President Obama’s father. Originally, White House officials told The Globe that the President had never met the elder Obama. But it corrected that statement two years later, after Omar mentioned during a deportation hearing that the two had briefly lived together. White House staff confirmed that the President had stayed with Omar when he first moved to Cambridge to attend Harvard Law School.

After Omar testified that he had lived in the U.S. for 50 years, paid income tax and been arrested on only this one occasion, a judge in Boston ruled that he could stay in this country, and even apply for citizenship. Administration officials have confirmed that the White House did not interfere in the case.

The law makes it clear that if Omar had committed an aggravated felony, the judge could not have decided to allow him to stay. Omar, like Bailey, would have been deported.

Leave a Reply