By Vittoria Elliott and Jennie Kamin

With Monday’s presidential debate looming, American constituents are paying close attention to one of the most contentious races in national history. In many ways, 2016 is a year of firsts: The first woman to win a major party nomination in a head-to-head match up, running against what, many would say, is the most inflammatory candidate in recent election history. And so far, both of them are the two least-liked candidates in modern memory.

Though now a standard practice in the presidential race, the television debate is relatively new. A purely American invention, the debates can make or break a candidate’s campaign. Here are a few highlights from history:

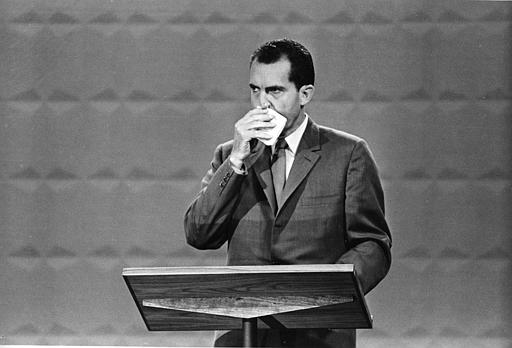

1960: John F. Kennedy vs. Richard Nixon

By 1960, TV ownership had exploded; nearly nine out of ten U.S. households had a television set. While Nixon performed well, making substantive arguments and leading radio listeners to name him the victor, he was hampered by the new medium’s emphasis on appearance. While Kennedy appeared youthful, cool, and collected, Nixon had to repeatedly wipe sweat from his face. The TV audience—an estimated 66.4 million Americans—took notice. Nixon lost the election by a close margin.

The country’s first televised presidential debate would also be its last for 16 years. At the time, according to Craig LaMay*, an Associate Dean of Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, “the debates were technically illegal.” FCC rules dictated that the press give equal time to the coverage of both candidates, with exceptions made only for “bona fide news events.” Debates, at the time, were not considered news events and Congress had to allow for a one-time exemption for the Nixon-Kennedy debates.

In 1964, incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson refused to debate his pro-states-rights opponent, Barry Goldwater. Scarred from his experience in the Kennedy matchup, Nixon followed suit, refusing to debate on television both in 1968 and 1972.

1976: Gerald Ford vs. Jimmy Carter

It was a revised FCC regulation, which designated presidential debates as news events, that revived the television debate format. Down 32 points in the polls against Jimmy Carter in the 1976 elections and desperate for a bump, Gerald Ford hoped that a televised debate would improve his image.

Though LaMay asserts that debates don’t change minds, merely confirm opinions, he also says, “You can’t win a debate, but you can sure lose one.”

LaMay points to Ford’s now-infamous gaffe where he declared, “There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe.” At the time, Soviet military presence in the region was globally evident. To this, New York Times reporter and moderator Max Frankel famously replied, “I’m sorry, what?” Ford lost the election by a narrow margin, a comeback he later attributed to the televised debates, asserts LaMay. And from then on the debates became a fixture of the American presidential campaigns.

1984: Reagan vs. Mondale

At the time of the 1984 election Ronald Reagan was 73, the oldest person to have been a nominee for a major party. After floundering in the first debate, Reagan essentially closed the age debate with a well-executed counterpunch, saying, “I will not make age an issue in this campaign. I will not exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience.” It got a huge laugh and the issue was defused. Reagan’s acting experience meant he knew how to work with a camera, too, arguably contributing to his success. He went on to destroy Mondale in the election, winning every state but Minnesota.

2000: Al Gore vs. George W. Bush

In a neck-and-neck election, Gore’s debate performance was, at times, overshadowed by shots of his reactions when his opponent, George W. Bush, was speaking. Gore’s sighing, eye-rolling, and sometimes indignant facial expressions came off as condescending to a number of viewers. Bush won the election by a narrow margin.

2016: Hillary Clinton vs. Donald Trump

Who knows? But when evaluating the playing field of the upcoming debate, Lamay’s assessment is unambiguous: If anyone can lose this debate, it’s Hillary Clinton.” LaMay notes that Trump’s public image seems impervious to criticism. “The only thing he did in the primary debates to suffer backlash was… essentially calling [Carly Fiorina] ugly.”

Clinton, he goes on to say, has to overcome two narratives: “One is that she’s a cold, unfeeling person. One is that she’s a weak woman.” Whereas no matter what he does, he adds, people expect Trump to be “bombastic.”

LaMay cites Clinton’s gender as an additionally troubling variable. “Much of the difficulty Hillary Clinton has had as a candidate is simply to the fact that she’s a woman.”

Though some speculated that Trump might dodge the debates, that’s historically been a poor move. President Jimmy Carter, who refused to participate in the first debate of the 1980 campaign because independent candidate John Anderson had been included, later lost to Ronald Reagan. George H.W. Bush was heckled by people in chicken suits when he suggested he might abstain from the 1992 debates.

Participation and performance in the debates can be critical, LeMay says, and they are a bulwark of our democracy. “Our campaigns suck by every other measure,” he says, referencing attack ads and massive campaign contributions. “The debates are the one part that’s dignified and serious. There are 78 countries that now do leader debates. If Americans can’t feel good about the election, they can be proud of the debates.”

* Craig LaMay’s name was misspelled in an earlier version of this story. We regret the error.

Leave a Reply