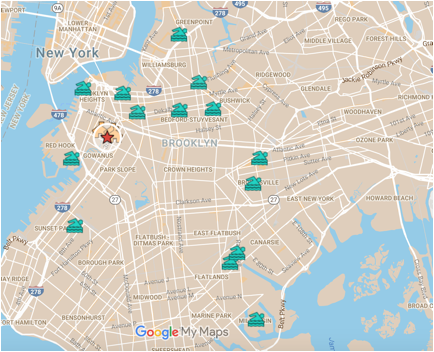

Brooklyn’s Public Pools. Red denotes the Douglass & Degraw Pool at Thomas Greene Park (Jennie Kamin)

For Gowanus residents, the swimming pool at Thomas Greene Playground is one of the few in the neighborhood where they can beat the summer heat. And they do. According to Sam Biederman, Assistant Commissioner for Communications at NYC Parks, this summer some 28,000 people visited the Douglass and Degraw Pool at Thomas Greene Playground, affectionately known by its neighbors as “Double-D Pool.” It is just blocks away from three NYCHA housing projects.

But how long will it continue to welcome swimmers? The answer is murky. Due to its status as part of an EPA superfund site, the future of the pool remains in question.

The 75 ft.-long pool sits just off of Nevins St. in the heart of a neighborhood known for its water contamination problems, notably in the nearby canal that gives the neighborhood its name. The canal is an EPA superfund site—thanks to the residue of multiple industries.

One of those industries was Brooklyn Union Gas, which later became National Grid, a natural gas and electric company. Its predecessor (Brooklyn Union Gas) left a bed of toxic coal tar that spans the entire length of the Double-D Pool and sits right below it.

The pool’s concrete barrier is about all that stands between the water and the bed of coal tar, according to a statement released by the Environmental Protection Agency. According to Walter Mugdan, the EPA’s Emergency and Remedial Response Division Director, the coal tar is as close as 20 feet from the surface.

But According to Elias Rodriguez, Public Information Officer for the EPA Region 2, the EPA is not concerned about the coal tar breaching the pool’s barrier. Rather, the agency believes that the carcinogenic substance presents a danger for the Gowanus Canal, about 300 feet from the pool. “The EPA has determined that there is leaching of the product into the Gowanus Canal,” says Councilman Stephen Levin, whose District 33, includes the neighborhood.

The solution? Due to the possibility of the coal tar further contaminating the canal, the city plans to excavate the ground under the pool, which could put the pool out of commission for several years, according to multiple reports. Because the city is waiting to found a replacement location for the pool before it excavates, it is hard to know when swimmers could expect a new one.

Meanwhile, the pool’s future is complicated by a second challenge. The Gowanus Canal is also contaminated by sewage coming from “combined sewer overflows,” according to Rodriguez. The EPA plans to prevent further contamination by installing retention tanks to store sewage, which, in its uncontained state, flows freely into the Gowanus during times of heavy rain. According to Rodriguez, “the use of retention tanks…is a feasible and commonly used remedy in urban settings throughout the country,” citing examples in Boston and other large cities.

To avoid complications with eminent domain, the EPA suggests placing the tanks underneath Double-D Pool, given that the ground under the pool is already planned to be removed. “Granted the site would already have to undergo construction, the EPA sees an opportunity in placing sewage tanks underneath the pool required in the maintenance structure of a newly-dredged Gowanus Canal,” says Rodriguez.

But the retention tanks, which Councilman Levin calls “quite enormous,” could also contribute to a jurisdictional issue over the pool’s rebuilding. “The question then becomes: whose responsibility is it to site a new pool and pay for it,” says Levin. He estimates that a new pool could cost tens of millions of dollars.

Not everyone wants the tanks under the Double-D Pool, however, and if neighborhood activists and City officials prevail in their push to base the retention tanks on an alternate site, the City would be charged with finding a replacement pool, in what is already limited space in the Brooklyn area. While National Grid is one of the Potentially Responsible Parties (PRPs in the lingo of the law) accountable under the Superfund Law for funding the cleanup, Rodriguez says that the sewage issue is the responsibility of New York City, which “has operated along the canal for many years,” referring to the combined sewer overflow system. In other words, when the city’s wastewater system begins to overflow due to rain, the system pushes some of the combined rainwater and sewage into the canal.

According to Natalie Loney, an EPA Community Involvement Coordinator, the city is working toward choosing an alternate location for the Double-D pool. Before beginning the cleanup, the EPA would have to find a location for the replacement and finish its construction. Obviously, that could take a while.

Leave a Reply