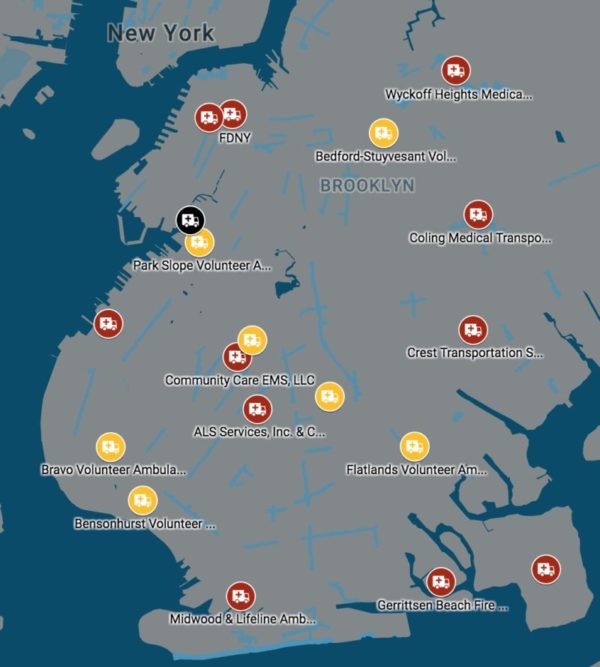

Ambulance services in Brooklyn, with municipal, hospital-based, and private services in red, volunteer services in yellow, and bankrupt TransCare Services in black (map created by Kaitlin Cough using Department of Health data)

You’re lingering over brunch when you choke on a peanut. You hit a pothole on your bicycle and go over the handlebars. You slip while ice skating in Central Park and hear a disconcerting snap in your arm. Somebody calls 911. Now what?

The wail of a siren is a backdrop to life in New York—the city operates the largest emergency services system in the country, responding to more than 11 million calls each year. In Brooklyn alone, 911 emergency services teams responded to more than 575,000 incidents in the past 12 months, 30% of which were life-threatening.

Calling 911 sets into motion a vast machine involving seven different systems and numerous city agencies.

A 911 Call Schematic (Emergency Medical Services Computer Aided Dispatch system (EMSCAD) is an FDNY system. NYPD ICAD is Intergraph Computer Aided Dispatch system. PSAC 1 is Public Safety Answering Center. (Source: http://www.nyc.gov/html/911reporting/html/anatomy/call.shtml)

This is a process so complex that the city set out to overhaul it in 2004—a project that was halted in 2014 after years of delays and coming in nearly $1 billion over budget—and has still not been completed. The way it works now if you call 911: a dispatcher in a call center nearest you, such as the MetroTech center in Brooklyn, handles most of the calls for NYC. The dispatcher takes your information and determines the severity of the emergency, assigning it a “segment.” Cardiac arrest and choking constitute segment one, setting crews off with particular fervor. Things like anaphylactic shock, asthma attacks, and major burns are also listed under the life-threatening category, in segments one through three.

After you’ve been assigned, the dispatcher puts out a call to the emergency services teams in the area. The closest ambulance that can provide the appropriate level of care (ambulances are staffed with emergency services personnel with different levels of training, from emergency medical technicians to advanced emergency medical technicians, also known as paramedics) sets off. Ambulances operating under the 911 umbrella may come from anywhere*, but services that are not part of 911 have a particular geographic area that they stay within—for good reason, notes Fred Kneitel, administrator at Brooklyn College Emergency Medical Services, a volunteer EMS team. “Every ambulance has its own geographic response area, and it has to be strictly adhered to, otherwise people would be stepping on each others’ toes. It would kind of be like the Wild Wild West.”

NYC separates ambulance services into four different types—hospital-based, municipal, proprietary, and volunteer. The FDNY and NYPD are the two municipal ambulance services, and along with hospital based services (private hospital ambulances that voluntarily participate in the 911 system), operate the majority ambulances on the streets. All municipal EMS services can be reached by calling 911, but other services “can work with the FDNY and State Department of Health to enter into the 911 system,” according to the FDNY. In 2010 the Wall Street Journal reported that, of those ambulance services under the 911 umbrella, the FDNY ran the majority of tours (shifts) in the city—64 percent—while the remaining 36 percent were spread among 25 private hospitals.

Outside of the 911 umbrella, private companies and unpaid volunteer crews also play a substantial role in getting ill and injured citizens medical assistance. Out of the 28 ambulance services (this includes all ambulance companies—private, municipal, volunteer, and hospital-based) licensed to operate in Brooklyn as of July 2016, 20 listed a ten-digit number as their emergency services number (rather than 911), and half of those non-911 services were volunteer.

Volunteer emergency services are community-supported endeavors, funded through grants and donations. They often have just one or a handful of ambulances at their disposal, and generally are not open 24/7. Volunteer ambulance services are usually staffed with basic EMTs*, and often charge reduced fees or no fees at all, which may be a welcome benefit in an industry where charges can be opaque and vary wildly. (In 2012, a report by the government accountability office found that it cost anywhere from $224 to $2,204 for a ride to the hospital).

Fred Kneitel stressed that it doesn’t matter who picks you up—city, private, or volunteer—all emergency services personnel are committed to providing the best care that they are able to. “Everybody gets the same care—it’s based on availability and the closest ambulance. One day the matrix could be so busy a unit could just be further than you want it to be.”

Kneitel grew up in Sheepshead Bay, and has been working in emergency medical services nearly his whole life. He remembers the shoreside volunteer ambulance services that served his town growing up, but worries that those companies are disappearing with changing communities and a dip in volunteerism. “College students today are very different from those in my day. Brooklyn College is a commuter college—they come and then leave. In my day it used to be that you would stay and study after class, hang out with friends, and be part of the community, but now you don’t need to stay on campus any more….Things are a little tough. Volunteerism is on the decline.”

The model for emergency services is indeed changing. What was once mainly under the purview of city services is increasingly being handed over to private firms, some of which are running into trouble. TransCare, a subsidiary of Patriarch Partners run by “Wall Street’s Wonder Woman,” Lynn Tilton, operated 27 ambulances in New York when it abruptly filed for bankruptcy last February. Overnight, 81 ambulance tours (each tour is an eight-hour shift) were taken off the streets, most of which were operating in Manhattan and the Bronx.*

FDNY spokesperson Frank Dwyer declined to speculate on the role private companies should play on city streets, but said in a statement that the FDNY was aware of TransCare’s struggles and had “contingency plans in place to respond” to the closure, with other teams in place for the routes run by TransCare ambulances. Data indicates that response times have indeed held steady in the wake of the TransCare bankruptcy, suggesting that emergency departments across the city have been successful in absorbing the shock.

But the company’s filing did raise questions about the role of private firms in providing essential public services. TransCare holds other contracts with the city, including a $150 million Access-A-Ride contract with the Metropolitan Transit Authority, which has also been plagued with service problems.

Please note—Three corrections/clarifications:

*this has been changed from the original, which indicated that hospital based services also restrict their geographic area

*this has been changed from the original, which indicated that volunteer ambulance services are often staffed with paramedics

*TransCare and its subsidiary, TC Ambulance Corp. continued to be listed under the city’s certified ambulance services list as of July 2016, with services licensed out of Brooklyn although the company lost its contract with the borough several years prior

Leave a Reply