On Sept. 13, Community Board 2 of Brooklyn overwhelmingly approved a $10.5-million-dollar plan by the Parks Department to renovate the northwest entrance of Fort Greene Park. It is the kind of investment that most neighborhoods would welcome, yet around Fort Greene, the plan sparked opposition that was only resolved when city officials made a concentrated effort to meet community leaders and citizens halfway. Fort Greene, it seems, doesn’t take changes to its beloved park lightly.

Last year, after a formal nomination process, Fort Greene Park was awarded a grant via Mayor Bill de Blasio’s $50 million dollar Parks Without Borders budget. A plan was soon developed by the Parks Department to open up the entrance on the Myrtle Avenue and St. Edwards Street corner by knocking down a five-foot high stone wall that’s roughly 40 feet wide. The department also proposed to level numerous stone-bordered grassy mounds that had been installed in the 1970s, and to build a new promenade of smooth concrete—while also installing 90 new gingko trees that will connect to the steps leading to the towering Prison Ship Martyr’s Memorial.

Aside from enhanced aesthetics, the stated goals of the Parks Without Borders project are to “improve park entrances, edges, and spaces adjacent to parks.” City officials note that refurbishing the northwest side of the park would be an investment in an area bordering the Ingersoll and Walt Whitman government houses. “A fair amount of money has been invested into Fort Greene Park over the last 15 to 20 years, but not a lot has gone into the Myrtle Avenue side,” said Rob Perris, the District Manager of Brooklyn Community Board 2. “This development changes that trend and invests capital into the side where the NYCHA apartments are.”

Fort Greene Park is a major landmark in Brooklyn. Any vote to alter the park was sure to generate interest and debate. Spanning 30 acres over an array of rising green fields and sloping hills; filled with hundreds of gingko trees and the distinctive Prison Ship Martyr’s Monument; and home to six tennis courts, barbeque cookout stations, and a full-court basketball blacktop; the park is a major center for daily recreation and weekend community events.

And indeed, almost immediately upon the plan being made public, Fort Greene residents answered with skepticism. For some, gentrification remains a concern with any sort of new development project affecting low-income neighborhoods, while for others, doubts rested on the question of whether the city could do the job right.

“I don’t doubt that the corner needs work, but I’m concerned by how the construction will serve the neighborhood,” said James Hannah, 49, who was interviewed in the park. “Is it going to engage the community or be a way of saying ‘Stay out’ to certain groups?”

“Government isn’t in the benefit of the people,” said Damali Elliot, 29, a Fort Greene resident. “It just seems like they’re mainly trying to keep with all the high-rises going up around us and cater to a new group of people.”

“I’m suspicious,” said Lieba Sutherland, 55. “The city’s already taking so much property from us. I’m worried about them not completing it and not having quality work done.”

But instead of gearing up for drawn-out fight over whose park it was, the Parks Department sought to engage with citizens about the renovation plan over a period of months.

According to Maeri Ferguson of the city’s Press Office, the Parks Department hosted three public meetings—Nov. 2, 2016; Feb. 16, 2017; and May 3, 2017—and continued to hear feedback at a June 19 Parks Committee meeting and a June 26 community board meeting. Attendance ranged from some forty to more than 100, and according to Ferguson, the main priorities people from the community expressed during these meetings were improving the northwest plaza’s aesthetics, improving physical access to the northwest side, restoring the view of the Martyr’s Memorial, and creating more usable space.

Despite all the effort to explain the plans, some locals still objected. According to a report by Patch.com, one Fort Greene resident, Lisa Hsu, garnered the signatures of 500 citizens opposing the project and filmed more than 20 YouTube videos of residents stating why the northwest corner of the park should not be leveled. “It’s going to disrupt all those things that our kids love,” said Brittney Granden in one video. “I’d just prefer it to stay the way it is.”

Furthermore, the Historic Districts Council, a nonprofit advocate for New York’s historic neighborhoods, took a shot at the plan, releasing a statement before the vote opposing the fix—for history’s sake. “The proposal appears to treat historic features of the park cavalierly and not take into account how the community uses the park,” wrote the group’s Executive Director, Simeon Bankoff.

In response, the city began to point out that redevelopment projects in Fort Greene Park have been a continuous reality since the park first opened in the mid-1840s. “Change is unsettling,” said Perris. “But this park in particular has undergone a series of changes over the years that aren’t all evident simultaneously.”

Perris, a landscape architect by training, noted that Fort Greene Park has undergone four different design periods since its inception: First came the original 19th century design by Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted; then Stanford White added classical elements like the grand staircase and Doric columns; Robert Moses’ City Parks movement in the 1940s brought recreational features like the tennis courts; and in the 1970s architect A.E. Bye put in Modernist renovations like gingko trees.

“To get too attached to a not too particularly important design feature is to not have a proper perspective on its context within Fort Greene Park,” said Perris.

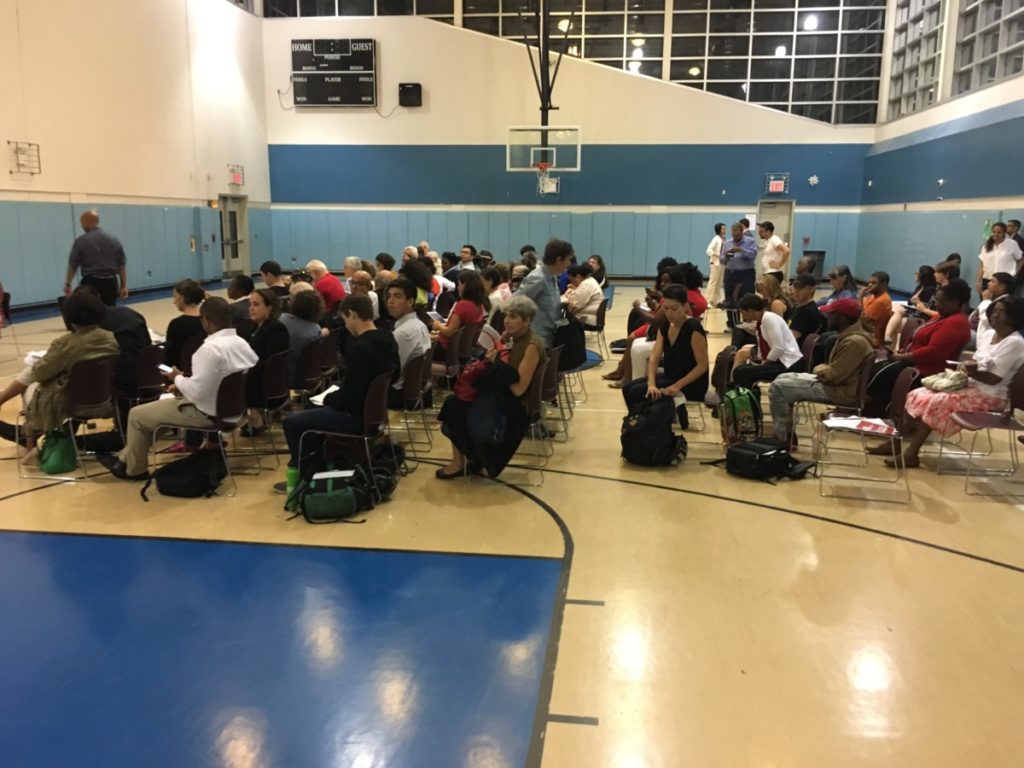

The debate over the Park’s future came to a head at a Community Board 2 meeting on Sept. 13, at the Ingersoll Community Center. Roughly 90 people attended, including CB2 board members; the City Parks Commissioner, Marty Maher; State Senator Velmanette Montgomery; State Assemblyman Walter T. Mosley; employees of the Fort Greene Park Conservancy; and numerous Fort Greene residents.

For nearly two-and-a-half hours, city officials, board members and citizens engaged in a spirited dialogue about the nature of the renovation proposal, whether the city could be trusted or not, how the trees would be replaced and cared for, and what assurances the city could give skeptical citizens about the mitigation of damage to public land. The tone was almost always civil, speakers took their turns, and at times laughter could be heard. City officials provided clear explanations and community leaders gave the positive endorsements. They noted that Maher had taken Mosley, Montgomery, and CB2 board members on a tour of the park the week before, which helped answer many questions surrounding the project.

In the end, the plan was approved— one vote abstaining, one vote recusing, and all others voting in favor. Claps and cheers from those seated in attendance followed the gavel slam by the Chairperson, Shirley A. McRae, indicating the end of the meeting.

“All summer long, we have had the pleasure of speaking directly with local residents on site about future plans for the northwest corner of Fort Greene Park,” Maher said in a statement following the vote. “Now it’s time to get to work and create a space everyone can be proud of and enjoy for years to come.”

According to the Parks Department, the project’s design is expected to be finished by late spring 2018, with construction anticipated to begin between spring and fall 2019.

Leave a Reply