For years, the Green-Wood Cemetery had been eyeing the object of its affection, the Weir Greenhouse, directly across from its gates on Fifth Avenue in Sunset Park.

When the cemetery’s president, Richard Moylan, finally proposed to buy the graceful greenhouse in July of 2011, he told The New York Times, it’s “something I’ve always wanted.” The Green-Wood historian, Jeff Richman, sounded similarly smitten, cheering the sale’s consummation on his blog, “It Is Ours!”

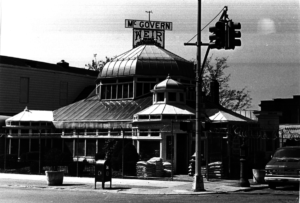

Maybe, but a public celebration of this union has been a long time coming. More than six years after the sale, Weir Greenhouse—the only remaining commercial Victorian greenhouse in all of New York City—stands encased in 15-foot-high fencing and scaffolding. Its rare beauty, recognized by both the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission and the National Register of Historic Places, is hidden except for its two copper cupolas. And no one at Green-Wood Cemetery seems to want to talk about it.

The course of true love never did run smooth.

The Weir Greenhouse would turn heads on any street, but particularly from where it sits today between a bakery and an auto repair shop. It combines bold form, as in its large octagonal dome, with the delicacy of a wood-frame and glass structure. It’s both simple and complex. Basically a rectangle, it is “enlivened by projecting bays,” as the Landmarks Preservation Commission described it. Particularly delightful is the unexpected way its entrance juts out diagonally onto the corner of Fifth Avenue and 25th Street. The entrance is shaped like an octagon, with its own miniature dome. It is clearly not your usual front door. For all its boldness, the greenhouse is quite petite, about 50 by 52 feet.

The Weir Greenhouse was built in 1895. Victorians of this era loved flowers, something that had allowed the Weir family to expand its florist business throughout Brooklyn and to build their own greenhouses. By 1886, James Weir, Sr. and his two sons owned 25 of them in Bay Ridge, as well as several nurseries in New Utrecht (Bensonhurst today), according to the Landmarks Preservation Commission. James Weir, Jr. branched out with a successful business of his own that culminated in the construction of the Weir Greenhouse. For this special structure, the younger Weir did not hire a greenhouse designer, but instead retained a Manhattan architect, George Curtis Gillespie.

From the beginning, the destiny of the Weir Greenhouse was entwined with that of the Green-Wood Cemetery, which was founded in 1838. According to an article, “Mourning Customs in the Victorian Era,” published by the National Park Service, the period marked the beginning of the custom of laying flowers to honor the dead. Flowers were so important that photos were taken of them and made into parlor cards for family and friends. “The show of flowers at a funeral was a visual reminder of the respect and the prestige awarded to the deceased,” the article said, and so the Weir Greenhouse thrived as baseball legends, politicians, artists, and inventors joined the Civil War generals buried in the vast cemetery across the street.

Green-Wood was also popular with the living. In fact, The New York Times reported that as early as the 1860s, “it had become one of the country’s premier attractions, ranking up there with Niagara Falls.” After a stroll in the parklike setting of the cemetery, Victorians would have enjoyed a visit to the greenhouse to buy blossoms. Etiquette of the era stipulated that only married women should wear jewelry, so young, unmarried women wore flowers in their hair or pinned small bouquets of sweet-smelling roses, violets, or geraniums to their dresses. Whether they wanted to communicate “love” (flowers worn over the heart) or “caution” (flowers in the hair), the Weir Greenhouse had what they needed.

The florist business began to decline in the new century, however, and so did the fortunes of the Weirs. The business was sold, and the greenhouse fell into disrepair. Though the flower trade was down, more and more people—around 250,000 annually—came to visit Green-Wood. Today among the hillsides, ponds, and paths are the gravesites of not only 19th-century luminaries, such as Boss Tweed; Louis Comfort Tiffany; Horace Greeley; and Teddy Roosevelt’s cherished first wife, Alice, but also those of more contemporary glitterati, including Leonard Bernstein and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Green-Wood’s impressive collection of papers, photographs, paintings, and sculpture also grew.

The cemetery badly wanted a visitor center, which could also serve as an exhibition space, archive study center, and library.

And soon enough, the Green-Wood Cemetery president, Richard Moylan, began to imagine one—right across the street. That was the vision for the Weir Greenhouse when he proposed to purchase it in 2011. As it turns out, it has been hard to make this dream a reality.

The first snag came with the architectural plans for the renovation of the landmarked greenhouse and the design of the new building that would sit beside it it to house exhibitions, archives, meeting spaces, and offices. (The city requires owners of a landmark or those planning to build on a landmarked site to get a special permit before doing any work.) In December 2013, Green-Wood’s architect, Page Ayres Cowley,

(photo courtesy of Andrew S. Dolkart, NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission)

presented her plans to the Landmarks Preservation Commission. At the commission’s public hearing, the commissioners voted “no action.” That language was “code” for not liking the plan, according to Andrew Dolkart, a professor of Historic Preservation at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, who—as a matter of fact—had been the Senior Landmark Specialist at the Landmarks Preservation Commission and author of the original document designating the Weir Greenhouse a landmark in 1982. Generally, the commission doesn’t like to reject plans outright, he said. If they didn’t like what they saw, they’d give the architect the benefit to withdraw. And that’s exactly what happened.

All relationships have their ups and downs, and Green-Wood’s love affair with the Weir Greenhouse was no exception. After the setback with the Landmarks Preservation Commission, the cemetery got a financial boost. In February 2014, New York State awarded $500,000 for restoring the greenhouse, according to the NYC Department of Finance. Still optimistic, Green-Wood went ahead in 2015 and purchased an adjacent lawn and building from the Brooklyn Monument Co. on 25th Street for $1.5 million. (That was on top of the original purchase price of $1.625 million for the greenhouse.)

In 2015, the architect, who had gone back to the drawing board after “no action” in 2013, returned to the commission with a new proposal. It featured the greenhouse with a modern-looking, three-story building flanking it as an L at its back. This time, according to Curbed NY, commissioners rejected the proposal outright as a “hodgepodge,” saying the new building did not “integrate” with the greenhouse.

Later in the year, only the work on the greenhouse got the Landmark Commission’s green light. President Moylan told the Brooklyn Eagle that Green-Wood might hire a different designer for the new building.

But, once again, Green-Wood got good news about funding, when New York City designated $2,949,375 for the visitor center in March 2016. An additional hurdle was crossed when the building permit for the restoration of the entire greenhouse was issued in September, according to New York City’s job filings.

But, once again, Green-Wood got good news about funding, when New York City designated $2,949,375 for the visitor center in March 2016. An additional hurdle was crossed when the building permit for the restoration of the entire greenhouse was issued in September, according to New York City’s job filings.

More than a year later, work on the greenhouse is not finished, and there’s been no word about the new building.

Renovation of an historic building is painstaking, even more so when it’s a fragile greenhouse and landmarked. According to Professor Dolkart, such historic restoration projects are “complex.” Adam Hogan, the foreman on the site, said, it’s been “a hard process, detailed.”

That echoes the viewpoint of Ian Buckley, an engineer with expertise in historic refurbishment who works for Arup, a global engineering firm. The first challenge of any project like this, he said, is to increase the façade’s ability to support the weight of the building. But that doesn’t mean a wholesale replacement of beams.“Rigorous structural analysis allows us to apply a ‘light-touch’ strengthening’ only to parts of the framing (such as the joints or the foundation),” Buckley said. Engineers also have to balance keeping original detailing versus giving a future architectural historian or structural

engineer the ability to see what’s been done. So, an engineer might use bolted plates where rivets were used originally. They also have to meet all modern code requirements.

All of this takes time, knowledge, and careful decision-making.

And it takes money. Altogether, the construction costs estimated in the ten building permits filed with the City for the Weir Greenhouse restoration totaled $1,748,800. Add to that the price to acquire the greenhouse and the adjacent building. The grand total comes to $4,873,800, without any cost overruns on construction.

Will it get finished soon?

Passersby, the construction foreman, and the volunteer handing out maps of the cemetery across the street are all optimistic about an opening of the Weir Greenhouse this year, but Green-Wood, alas, won’t commit to a date. What’s certain, though, is that it will warrant a celebration…with lots of flowers.

Leave a Reply