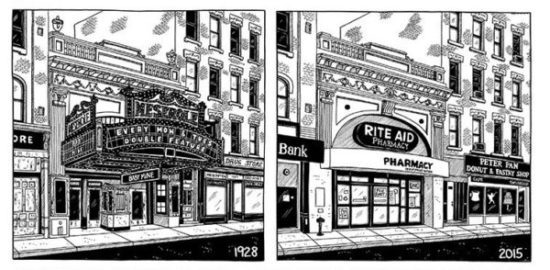

You could easily walk past the Rite Aid on Manhattan Avenue in Greenpoint without giving it a second look. Only from across the street do you notice the triumphal-arch-style stonework still intact over the store sign. The building is short and squat, and the combination of old and new is strange but initially unremarkable. But when you venture inside, perhaps searching for some potato chips or toothpaste, you get a sense of the way in which the building continues to inelegantly bear its history.

The structure, near the intersection of Manhattan and Meserole Avenues, has housed various pharmacies for the last three decades, but if you look up from the stained rugs and rows of merchandise you can see the Georgian arches, molding, and giant dome that evoke the building’s 50 years as the Meserole Theater. Clashing with that aesthetic is a giant disco ball hanging from the center, reminding you of the space’s brief tenure as a roller rink in the 1980s.

And now, people who know the place can at least dream of it returning to its past glory, hoping that it can someday be used as a theater once again.

The Meserole certainly isn’t the only theater to be converted to other uses in the neighborhood, but it’s the only one that feels as if its current use is only temporary. Other spaces, like the nearby former Chopin Theater, also on Manhattan Ave.—now housing a Starbucks and a New York Sports Club—only retain a superficial sense of their past, for example by retaining the facade and marquee. Inside, they can’t be distinguished from any other franchise. Here, by contrast, you can almost see the way in which the seats were cleared and the stage torn down to make room for roller skaters, and later, toiletries and cleaning supplies. The mezzanine section is intact, partially blocked off. The building is clinging to its past as best it can.

This could be the prime moment for the space to enter the next phase in its life. Rite Aid has sold almost 2,000 stores to Walgreens, but this isn’t one of them. The street already has another location for both brands, and according to Nicole Rabinowitsch of TerraCRG, the location can be delivered vacant. The building’s fate is up for grabs.

—

The Meserole Theater derives its name from the mansion that stood in its place beginning in 1790. The Meseroles were one of Greenpoint’s original families, and the Adrian Meserole House served as its farmhouse. It was demolished in 1919 and the theater, designed by Eugene DeRosa, opened in its place two years later, according to the Brownstoner.

What many don’t know, according to Geoff Cobb, a local historian and high school history teacher, is that the Meserole began its life as a vaudeville theater. It was one of seven such theaters in the neighborhood. Though that seems excessive by today’s standards, the theaters were necessary to accommodate the incredibly dense neighborhood, where a single block could house up to 1,000 people, according to Cobb and data from the time. A ticket only cost five cents in those days. He guesses that the vaudeville stars of the day, like Mae West and Jackie Gleason, would have been among the performers to cycle through.

With the advent of silent movies, the theater—nicknamed “The Mezzy” by those who frequented it—became one of Greenpoint’s two first-run theaters, meaning it received films as soon as they stopped showing in Manhattan. Lifelong resident John Dereszewski says he, like many other young people in the neighborhood, had his first date at The Mezzy, which was considered the classier of the two establishments. “I don’t think there was another date with the same woman, but that’s another issue,” he adds.

Going to the cinema was a different experience in those days. Tickets were bought in advance and and the theater usually showed a double bill. “You really wouldn’t bother to look at the movie clock to find out if something was starting or not,” Dereszewski says. “They would let you go in. If it was the middle of the movie you would watch the end of it, and then you would see the second part of the double bill, then you would watch the first one that you saw until you came to the part where you came in and then you’d leave.” Unlike today’s multiplexes, the theater was a single hall that accommodated 2,000 people.

Cobb says that the neighborhood underwent massive white flight in the 1970s; the Meserole was no longer profitable and so it was sold. Dereszewski was “sad when it closed, but theaters were closing all over the place.” Capitalizing on the roller skating fad of the time, the space was converted into a rink in 1979, but “those things have a relatively short half life,” he says. Many of the building’s renovations happened during this time, including the removal of seats to create a flat floor (and the installation of that disco ball).

Ultimately that stage in the building’s life came to an end as well, and in the late 1980s the space transitioned once more into its current use.

But it retained its character. Usually when theaters are converted, “they do a real hatchet job,” Dereszewski says. But this case was different. “Whoever did it could have easily gutted the whole place, put in a drop ceiling. But for whatever reason, who knows why,” that didn’t happen, he adds.

The way in which the building’s grand dome hangs high above rows of shelving suggests that this is only a temporary stop in this building’s life. However, it’s as yet unclear what will happen to the old Meserole Theater. Those concerned can envision different scenarios.

Esther Crain, urban historian and founder of Ephemeral New York, finds some beauty in the building’s current situation, which reflects what New York is today. “I’m not somebody who thinks that all of New York City should be preserved as it was,” she says. “I actually think there’s something great in that it’s a Rite Aid. Not great because I love drugstores, but that is New York in the 2000s.”

Dereszewski fears that, like many buildings throughout Brooklyn, the Meserole will be converted into apartments, but he isn’t sure that it’s a good idea to return the theater to the way he remembers it either. “In my fantasies, bringing it back as a movie theater would be great. It’s probably too big,” he says, noting that it would have to be divided into sections that would obscure the space’s original beauty. If the building had hung on for a few more years, it might’ve been able to continue on as an indie house, he says. But practically speaking, Dereszewski believes the owners could make a few more restorations, but ultimately maintain the building’s use as a retail space. “Those of us who still remember the place can think back, and those who don’t can get a sense of what was there.”

Others hang on to the nostalgia of returning the Mezzy to its former glory, and some believe that this may actually be an economically astute decision. Ward Dennis, a historic preservation consultant, notes that these kinds of buildings are typically either rehabilitated for their historic use or re-purposed in a way that takes advantage of their large space. He points out that while the Meserole wouldn’t qualify as a landmark at this point, listing it on the National Register of Historic Places would mean substantial tax credits that would incentivize the preservation of the building.

Jennifer Schork, of Preservation Greenpoint, agrees, saying in an email that “as a preservationist and architectural conservator, the idea of it being brought back to its original use is not only very desirable, but also quite practical in terms of feasibility for rehabilitation.” She says that given its original design as a theater, with some updates “a restoration could bring it back to a very interesting and unique theater space.” Renovations would be expensive, of course.

Many theaters are coming back to other Brooklyn neighborhoods, and its possible that Greenpoint will follow that trend. Rabinowitsch, of TerraCRG, agrees. She says the neighborhod is transitioning much in the same way as Williamsburg has and would benefit from improved entertainment attractions of its own. “It would be a beautiful thing if they restored it to it’s original grandeur,” she adds. The closest multiplex is 20 minutes away, but caters to the much larger Williamsburg population.

Historian Cobb bemoans the fact that Greenpoint doesn’t currently have a movie theater or adequate performance venues—and he thinks the Meserole could serve that purpose, harkening back to its vaudeville days. “The community desperately needs that. This place is coming down with musicians, and there really isn’t a great music venue, so it would be perfect for that. For it to go back to its original use, that would be amazing,” he says.

(Top photo by Nafisa Eltahir/The Brooklyn Ink)

Leave a Reply