This summer, Hadi Nasiri, a 32-year-old artist from Bandar Abbas, Iran, moved into a light-filled studio at Westbeth Artist Community—one of the most coveted pieces of real estate in New York City. Nasiri spends his days making art, studying film at the New School, and cooking elaborate Iranian dishes in his studio kitchen. “I sleep about four hours a night,” he says. Along his kitchen shelves are an array of pickles—okra, cauliflower, garlic—that he makes himself. “The other night, I was lying in bed at 3 a.m., thinking about how the dish I had made for dinner could be changed. ‘What if I added a little more salt? Some lime? Cooked it this way?’ I kept thinking. I couldn’t go back to sleep until I had made it again, the way I imagined. Then I thought—why don’t I just make it again? I cooked until 5 a.m.”

Nasiri floats around his studio, beautifully dressed in loose-fitting dark clothes. He has a finely sculpted beard and his head is shaved but for one tiny patch. He is talking excitedly, drinking strong espresso and making the final preparations for brunch, Persian-style: a dark, rich stew of lamb’s liver and kidneys; fresh herbs; flatbreads with curd cheese and a bright, spicy green sauce; more coffee; sweet biscuits; challah bread; nutella. Sunlight streams in from the warehouse windows.

In many ways he lives an idyllic life, but it is also a life in limbo. Nasiri is in the throes of his asylum application, a process that has become all the more complex since Donald Trump’s inauguration.

The Brooklyn Ink

This is a catch-22 for outspoken artists like Nasiri, who come to the United States from countries where their work is censored. The likelihood is that once they arrive, they won’t be able to return home. In America, for the first time, such artists have the freedom to make controversial pieces and actively promote their work. Suddenly, they are on the radar: If they weren’t being watched before, they certainly are now. They face a choice. Apply–at length–for asylum, and never go home again, or risk returning to their countries and being persecuted for the art they made in America.

President Trump’s invocation of the Travel Ban in April—even though it is in legal flux after a federal judge blocked it in October, at least temporarily—complicates things further. Under the ban, it would be impossible for people from nations affected by the executive order to leave the States and expect to return. Such people cannot visit their families; their families cannot visit them. Visa applications are scuppered; asylum claims delayed indefinitely. According to a report by The New Yorker, asylum applicants fall victim to an understaffed, overworked immigration office, meaning the wait for clearance is becoming ever longer. “Under Obama, you knew the asylum process took around a year,” said Farideh Sakhaeifar, another Iranian artist at Residency Unlimited, an international artist program based in Cobble Hill. “Now, who knows how long it will take? Psychologically, this affects me on a daily basis.” According to Ashley Tucker, Nasiri’s lawyer at the Artistic Freedom Initiative, the wait now hovers around two years—and for those under the Travel Ban, the extra screening adds another layer of bureaucracy, stress, and time.

I’d hate for anyone to get hurt. There are radical people out there. It’s dangerous for a gallery to show my work.

Nasiri managed to evade prolonged capture as an artist in Iran. He says, casually, “I have been detained before, but they released me.” His lawyer wrote about how Nasiri was tortured at the age of fifteen for a speech he gave at school on women’s rights. “They tied him to a table, and poured boiling water over his stomach,” Tucker says. Some of Nasiri’s colleagues in Iran have been thrown into jail for up to twelve years for their work. The other problem in Iran, he says, was the uncertainty of never knowing who was watching. The Iranian surveillance state meant that an artist could never live and work in peace. “I had no idea how much they knew about me,” Nasiri said. “They wait for the right time to jump on you and make use of you.” But still, it was home.

Photos courtesy of Hadi Nasiri

In 2012, Nasiri was offered a residency placement in Saratoga, California. He accepted, intending to stay for three months. He brought just a few sets of clothes with him. But after he arrived in the sunshine state, he gradually began to realize that his hopes of returning safely to Iran were beginning to fade. The work he was making in America made him too vulnerable. “I had done too many crazy things,” he says.

For example: On the wall above Nasiri’s bed hangs a large canvas painting of giant penis beside a Campbell soup can spurting dark liquid. The testicles are covered in Arabic script that reads “In the Name of God.” In one corner of the painting is the Tahwid, an emblem of Iran. It’s part of a series riffing off Andy Warhol’s pop art—there’s also a fire extinguisher that’s been turned into a tin of Campbell’s “Democracy Soup,” with Barack Obama’s face where the trademark should be. Nasiri made the painting when he first came to America and realized he had left his old life behind. At that time, he was, in his own words, “so angry,” he said. “I had had my own life at home for twenty years.” Nasiri wasn’t looking for a new life in America: it just happened to him.

I feel strange when I have to mark a box saying whether I’m male or female—I’m both at the same time. I’m none at the same time. It’s the same for my nationality.

Nasiri is the guinea pig artist of the Safe Haven Artist Prototype, a New York City residency designed to provide sanctuary, protection, and shelter to artists who face persecution. *Although the project has been in the works for more than two years, Trump’s inauguration gave the artist community in New York a wake up call and provided additional impetus. “People were shaken up,” says Sebastian de Santamaria, who co-founded the program this summer out of his tiny office at Residency Unlimited in the former South Congregational Church in Cobble Hill. “It makes complete sense to create something that is a mirror of our ideology,” he said. Safe Haven is run collaboratively by Residency Unlimited, ArtistSafety.net, Artistic Freedom Initiative, and Westbeth Artists Housing. Together, the organizations work to support artists with legal, practical, and pastoral care, fighting legislation at home and abroad.

in religion.’ ” | Photo courtesy of Hadi Nasiri

It is something of a miracle that Nasiri himself managed to get out of the Middle East. His performance pieces there often put him in significant danger. One of the last performances he did before coming to the United States was See Me as I Want to Be Seen, for which he dressed up in a burqa, customized with a notebook-like headpiece featuring fashion portraits of Arab women’s faces. Wearing this disorienting ensemble, Nasiri went around the Masjed Al Haraam in Mecca City, Saudi Arabia, showing the different faces to passing worshippers.“It is unbelievable he didn’t get caught,” said de Santamaria, shaking his head in wonder. The performance was in protest to Saudi discrimination against women. “Women are never seen with makeup or dressed as they wish, nor are they allowed to express themselves,” the artist writes in his manifesto. Nasiri was fully aware of the dangers involved in the performance, noting the Saudi Arabian National Religious Guard’s recent arrest of a man “for smoking one mile away from Masjed Al Haraam. He spent one year in prison in addition to being tortured.”

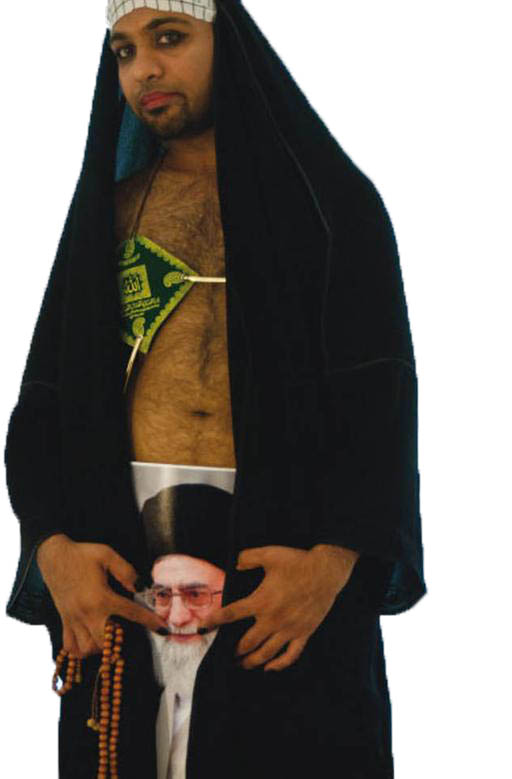

Another of Nasiri’s most provocative pieces was Bassij Cultural Production, a lingerie series “designed for a Muslim woman who believes ‘for the protection of body and soul one should find refuge in religion’.” The collection features bras made of miniature prayer rugs and healing shawls, with straps made from tasbih prayer beads.

Here in the U.S., Nasiri says he is concerned about drawing too much attention to himself—something pursued avidly by most of his creative contemporaries working in New York. “Can you believe I have never had a solo show?” he says. “I’d hate for anyone to get hurt. There are radical people out there. It’s dangerous for a gallery to show my work. All my pieces have been shown in public spaces—that’s where my audience is.”

These days, Nasiri says he doesn’t feel Iranian, or American—“I have no nationality,” he says. “I feel strange when I have to mark a box saying whether I’m male or female—I’m both at the same time. I’m none at the same time. It’s the same for my nationality.”

They’re not victims. They’re artists.

When asked whether he feels safe, Nasiri laughs loudly. “That’s a strange question. Ask me again after I do my next performance here.” But Nasiri is a cautious man—he has rules and structures in place, without which he admits he wouldn’t feel safe. He ignores emails sent to him by private galleries; he checks up on people who try to contact him. “He’s somewhat of a paranoiac,” de Santamaria says, smiling.

Nasiri is conscious of the reaction his work elicits—“When you’re talking about Islam you’re making 2 or 3 billion people your enemy. They are happy to see you die.” Nasiri hopes to use Residency Unlimited’s space in the nave of their Cobble Hill church building as a forum to try out his ideas for future exhibits, and maybe even to stage a performance this fall. He says he won’t let anything get the better of him or his work. “The only thing I live in real fear of,” he says, “is bed bugs.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: The wording in this sentence has been altered to show that the Safe Haven project has been in the works for more than two years, well before President Trump’s inauguration.

Leave a Reply