On Saturday mornings, when West Street in Greenpoint, Brooklyn is quiet and has few cars on the road, it appears to be the perfect place for a leisurely bike ride. But it is the weekday rush when things get dicey and delivery trucks can be seen parked in the raised bike lane, forcing cyclists into the road or onto the sidewalk. This is disappointing for locals, considering the recent completion of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway project, executed by the Department of Transportation and Department of Design and Construction, which promised to promote safe cycling along Greenpoint’s waterfront.

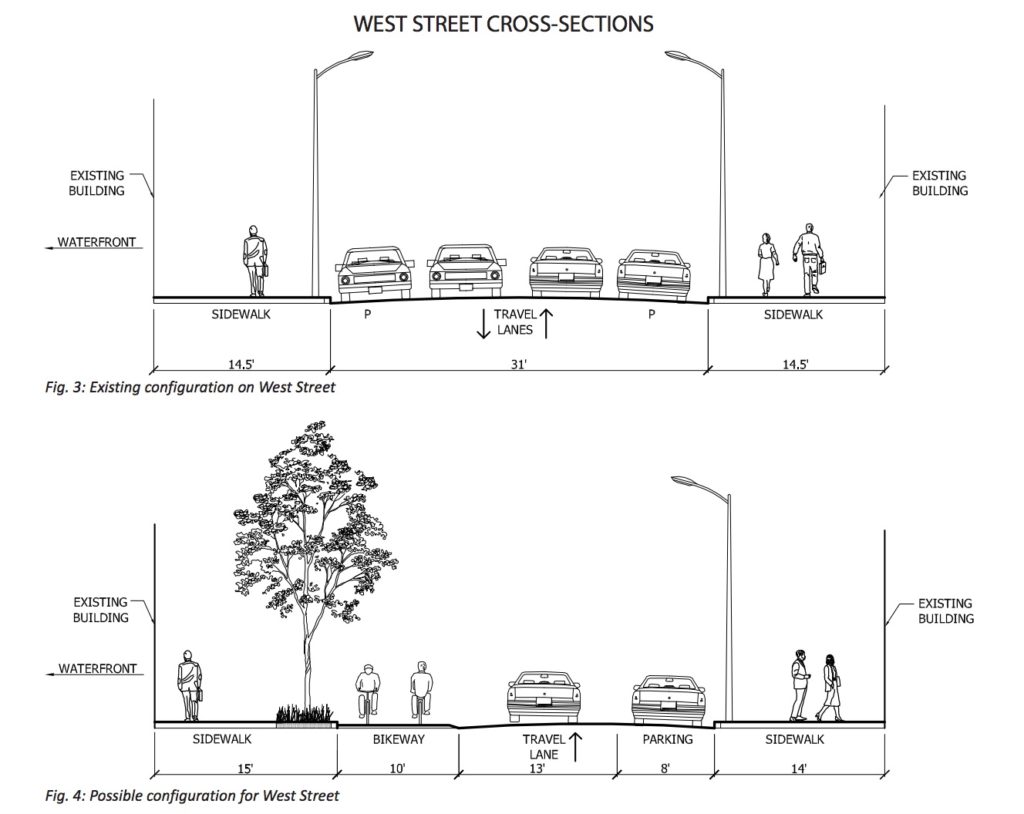

According to the initial project plan that addressed portions of the waterfront throughout Brooklyn, the West Street construction was estimated to cost $8.5 million dollars and would “widen the west sidewalk to include a two-way bicycle path” between Eagle Street and Quay Street.

Jon Orcutt, a Greenpoint resident and spokesperson for Bike New York, an organization that promotes ridership in New York City, says that money was wasted on the reconstruction. The path is “not useable” and is “chronically blocked” says Orcutt.

According to 311 records, complaints regarding blocked bike lanes in Greenpoint have significantly increased. Last year, 120 complaints were made, while this year, more than 300 complaints have been lodged so far. NYPD Captain William Glynn says that the 94th Precinct has received 170 calls specifically regarding West Street since the beginning of this year.

Calls to 311 trigger a patrol officer to respond and address the condition by either writing a summons or requesting that the vehicle move along. Some residents feel the response time is too slow.

“Most of the time if you call the police and say, ‘hey there’s this illegal trucking activity or someone endangering the lives of cyclists or pedestrians,’ they will get there in an hour or two hours after the person has left,” said Victoria Cambranes, a community activist and 2021 candidate for city council. By then, parking violators have moved on and the threat to cyclists is no longer imminent.

Bike New York does not believe ticketing is a significant enough deterrent for parking violators and would like to see the city build a barrier between the driver and the bike lane. But this plan poses other problems for delivery vehicles who still need access to buildings and loading docks.

Although James Wilson, a Greenpoint local, says he would feel more comfortable if bike lanes were protected, he has a forgiving view of truck violations on West Street, highlighting the tension between increasing delivery businesses, and the need for safety.

“The way the bike lanes are set up in the city are not well thought out, businesses have to make deliveries,” said Wilson. “To be honest I understand, there’s nowhere else to park and drop off.”

The 94th Precinct has taken steps beyond summonses to address the issue on West Street. At the end of September, Glynn and his community affairs officer sat down with local bike shop owners, bike advocates, as well as two representatives from the Department of Transportation. According to Glynn, there were about 10 people in attendance.

“It was a starting point for us to come together and come up with a better solution,” said Glynn.

The solution, which Glynn claims is already in the works, is an improved design from the Department of Transportation.

The Department of Transportation did not respond to inquiries from The Brooklyn Ink in time for publication. When asked about the bike lane’s construction and its inability to keep cyclists protected from motorists, Ian Michaels, press officer for the Department of Design and Construction, stated “This was built by DDC for DOT, to DOT specifications,” and did not know about any new plans to modify the bike lanes.

Cambranes has her own suggestion for how to address West Street, acknowledging that a protected bike route that upsets commercial trucks would likely not be viable.

She proposes making Franklin Avenue a one-way street with a double protected bike lane on one side with parking that separates the cycling route from traffic. This design is similar to that of Kent Avenue in Williamsburg.

“This would be a safer solution and much easier to implement than trying to skirt around West Street traffic, construction, deliveries, the film industry,” says Cambranes. “There’s just so much to navigate through there that you can’t do it legislatively or through city planning.”

More signage on West Street, indicating where trucks are permitted to park and outlining other rules of the road for cyclists and pedestrians, is another idea supported by Cambranes and locals have expressed confusion in these areas.

“I don’t even know what the laws are,” said Wilson pointing out a yellow dotted line running down the middle of a two way bike path, a no standing sign, and a truck parked in the bike lane.

“West Street probably doesn’t make or break cycling in New York, but it is a symptom of a greater problem,” said Orcutt, referring to bike lanes citywide. Broader New York City aside, in Greenpoint, West Street is not the only street with bike safety issues.

“The problem is really on Franklin Street because the road is so narrow – Franklin and Manhattan,” said Dave Magdaleno, another Greenpoint local. Magdaleno says he knew a father of three who died on Franklin Street and Magdaleno himself had a close call on Manhattan Avenue. While riding with his son, a parked truck opened their door into the bike lane without looking for oncoming traffic, luckily the cars behind him saw what happened and stopped.

That was the last time Magdalena says he rode his bike on Manhattan Avenue and he would not encourage anyone to venture there on a bike. He says he fears becoming the next “ghost bike.”

Leave a Reply