Oziel Arias was diagnosed with chronic asthma when he was five. Now nine, he sees the doctor once every six months and relies often on an inhaler. His diagnosis isn’t unique in East Williamsburg, the neighborhood where his family has lived since 1995. And some community members suspect they know the reason for that. They blame the waste transfer station nestled in the middle of their residential block.

The community has complained about the facility for more than two decades, to little avail. But the community is changing, and some of its new members bring additional resources to the fight. Ben Weinstein is an East Williamsburg resident and one of the leaders of Clean Up North Brooklyn, a neighborhood group founded in May 2015 that’s dedicated to getting Brooklyn Transfer, LLC, the company that runs the transfer station, to clean up its act.

Weinstein says that employees of the station regularly violate the rules of its permit. “The station openly breaks the law,” said Weinstein. “The permit is more like a list of false promises. And the rules are in place to protect the community but there’s no way to enforce them. If you call 311, nothing happens.”

The transfer station opened in the neighborhood more than 25 years ago, although it has changed hands several times since the 1980s. Five Star Carting Inc., a Queens-based commercial waste-collection company, has operated the station since 2010. A city law signed in 2004 bans heavy manufacturing facilities from being erected in residential neighborhoods, but Brooklyn Transfer, LLC is grandfathered in. The station moves more than 560 tons of waste per day.

When asked for comment, Brooklyn Transfer emailed a link to an interview with an industry newsletter. In an exchange with WasteDive, Nino Tristani, Brooklyn Transfer’s owner, told the newsletter, “Brooklyn Transfer is a properly licensed and permitted facility, with multiple inspections daily of its operations, facility condition, equipment, odors, and personnel by trained inspectors. Like our colleagues elsewhere around the city that operate similar facilities, we strive to be good operators, good neighbors, and good stewards of the environment as we perform essential services for the city. Unfortunately, the city’s land-use history, waste management plans, and current policies allow our operations—and many other industrial-type companies—to exist alongside nonindustrial uses.”

The members of Clean Up North Brooklyn recently released a report documenting more than 1,200 violations committed by Brooklyn Transfer, LLC in a single one-week period last May. Tristani denied the report’s allegations to WasteDive.

Still, neighborhood activists compiled the report by setting up surveillance cameras on the building across from the station. Volunteers then combed through video footage to tally the exact number of permit violations. Jen Chantrtanapichate, who founded Clean Up North Brooklyn in May of 2015, says that members used video footage to ensure that their evidence would be indisputable.

“This isn’t the first organized effort against the station,” said Chantrtanapichate. “I’ve spoken to my neighbors who have been in the community for much longer, and many of them have said they’ve tried. They’ve organized a march to city hall, they called the city, they protested it. But nobody cared.”

Osiris Arias, Oziel’s father, remembers these efforts well. “I went to a meeting with Congresswoman Diana Reyna six years ago to complain,” said Arias in Spanish. “Congresspeople are supposed to be for people, I thought. But nothing happened.”

Arias also says he tried calling 311, usually to no avail. But, he points out, there is a new element to the struggle. He says that people in the neighborhood have more faith that the city will pay attention to the fight—now that, as he put it, white people are involved. “People didn’t want to get involved but now that there are more white people in the neighborhood, there is more power,” he said. “We didn’t feel that power as minorities.”

Arias said that there used to be many neighborhood residents without legal status who were unwilling to sign a petition for fear that they would become targets. Now, he says, more of his neighbors have obtained legal status and are willing to show up for the cause.

Brooklyn Transfer, LLC is located only five minutes from the Morgan stop on the L train line. When it opened, the land surrounding it was cheap. And the neighborhood was overwhelmingly Hispanic. In the past 20 years, young Brooklyn transplants have been moving into the neighborhood at higher rates, resulting in an average rent increase of almost 79% in Williamsburg since 1990. These are the new neighbors to whom Arias says the city might finally listen.

Ben Weinstein says that attendees of Clean Up North Brooklyn’s community meetings are a mix of new and old East Williamsburg residents. He also says that those most affected by the transfer stations are the families who have lived in the neighborhood for many years and don’t have the resources to relocate.

*

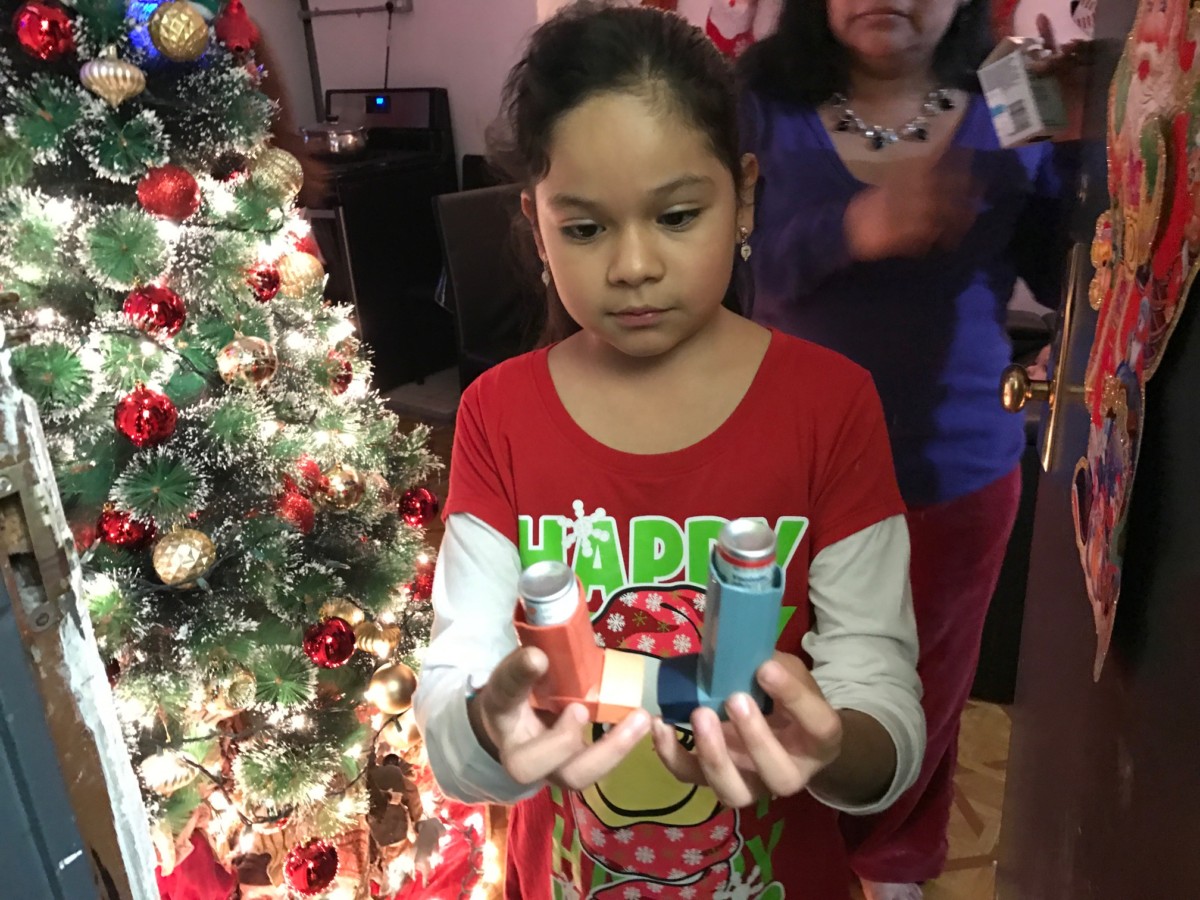

Directly above Arias’ Thames Street apartment is another apartment, small but cheerfully decorated for the holidays. Mercedes Tapia, who lives there with her husband and three daughters, has managed to fit a brightly-lit Christmas tree into a corner of the kitchen and a papier-mâché snowman hangs from the ceiling. But all is not well in the household. Her two eldest daughters have been diagnosed with asthma.

“When my first daughter came down with asthma, I didn’t think it was because of the transfer station,” she said in Spanish. “But my younger daughter was diagnosed when the buildings around us were coming together to try to remove the station so I started to think there might be a connection.”

Tapia says that although she has been searching for an apartment in different neighborhoods, her family has not yet found anything else they can afford.

She confirmed Arias’ account of previous efforts made by the community to hold Brooklyn Transfer, LLC accountable. She said that petitions were circulated but that at that time the people in the area didn’t have the resources necessary to organize the way Clean Up North Brooklyn is trying to do.

“Sometimes it’s hard for residents to come together because people are afraid or there’s a language barrier or they have to work and take care of their children,” said Tapia. “People have other responsibilities.”

Melissa Iachan, a senior staff attorney in the environmental justice group at New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, says this is exactly why facilities like this end up in these neighborhoods in the first place.

“When Fresh Kills landfill closed on Staten Island, these stations began popping up in low-income neighborhoods where the communities didn’t have the resources to object and where wealthy white neighbors wouldn’t cause an uproar,” said Iachan. “That’s why over 75% of New York City waste goes to three neighborhoods—the South Bronx, Southeast Queens, and North Brooklyn.”

A 2012 report released by SUNY Downstate Medical Center found that asthma rates are unusually high in North Brooklyn, the South Bronx, Harlem, and parts of Queens. They cite sanitation transfer stations as a contributing factor. In Williamsburg-Bushwick, the study found that people over 65 were hospitalized for asthma at three times the rate of other Brooklyn residents their age.

Iachan says there is no legal precedent for shutting down a waste transfer station due to community complaints. She says the neighborhood’s best hope is for the passage of Intro 495, a piece of legislation that would reduce the permitted capacity of waste at transfer stations in New York City. Iachan and NYLPI are working with city councilmembers in the most affected neighborhoods to get the bill passed.

Ben Weinstein contends that Brooklyn Transfer, LLC, is emblematic of a much larger waste inequity problem but it’s unique in regards to its proximity to the residential buildings that surround it. “We have yet to find another waste transfer station that has such a problematic setting and that’s a bitter pill to swallow,” said Weinstein. “The backyard of the facility is against homes and nowhere else in New York City is there a facility surrounded by residences on all four sides.”

As for Clean Up North Brooklyn’s next steps, Weinstein says the group has been invited to sit down with the New York Department of Sanitation to talk about enforcement. He says it has also received support from Councilman Antonio Reynoso, who represents Williamsburg and Bushwick. Above all, Clean Up North Brooklyn members say they intend to put pressure on the waste transfer station until it abides by the law or leaves the neighborhood.

“The community believes Brooklyn Transfer has had ample time to clean up their act but now we’re out of patience,” said Weinstein. “The city should revoke the permit. They had their chance.”

Leave a Reply