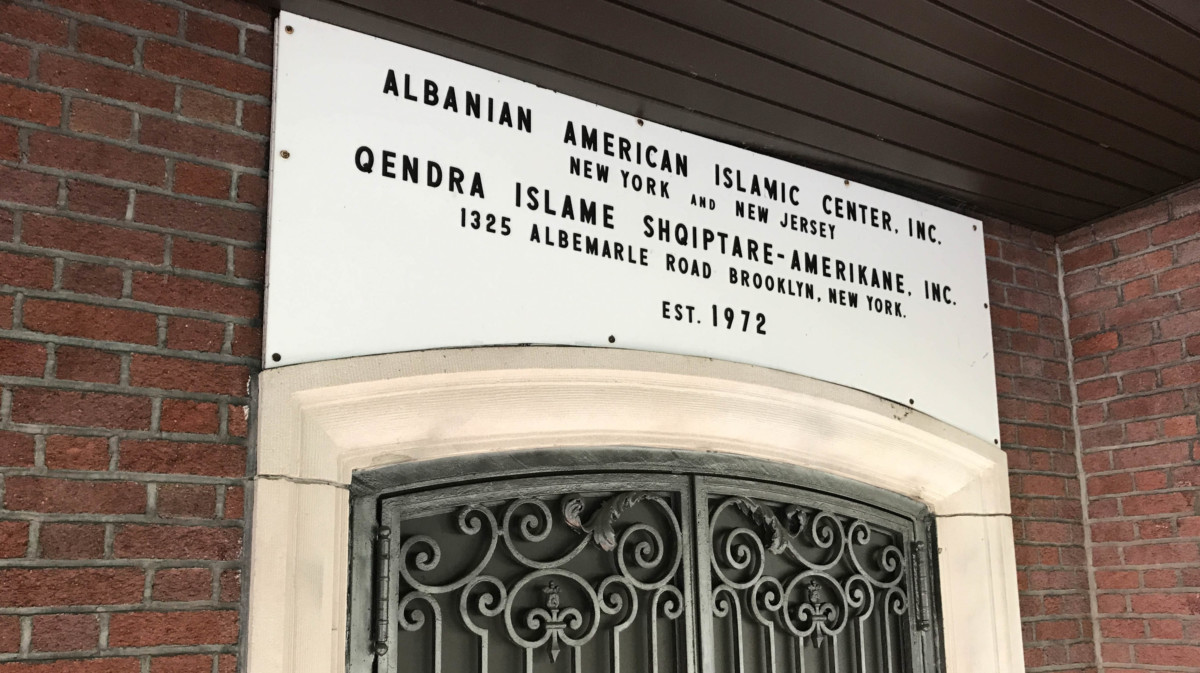

The three-story brick building on the corner of Albemarle and Rugby in Flatbush is so shrouded by two scarlet oaks that they cast a permanent shadow on much of the exterior. Long windowpanes bear a frosted finish, obscuring a look inside, sparking intrigue for passersby. The doors are locked. Beneath the veranda, inscribed in small black letters, the text reads, “Albanian American Islamic Center, Inc. EST 1972.”

It’s a Friday evening. Imam Roland Cinari hastens to unlock the mosque, his two little kids tugging on each arm, hyper from an eventful day at school. He was given the keys to the mosque seven years ago. Now at the age of 36, the young Imam is grappling with the question of how to keep the next generation of Albanians interested in Islam. “The masjid is the foundation, but you need a community,” says Imam Roland.

Once they all remove their shoes, he ushers his son and daughter inside, where they grab toy cars from a corner and begin to launch them across the prayer room. Otherwise, the place is quiet. About 80 to 90 Albanians had come for Jummah, Friday prayers accompanied by a sermon, earlier in the day. The Imam says a few others from different ethnic backgrounds joined as well. He considers that kind of turnout a sizable gathering. But throughout the week, the mosque remains mostly empty.

Imam Roland knows that he faces a major challenge. This is partly because Albanians have a complex relationship with faith. Albanian religiosity was fractured in 1967 when the Communist Party declared Albania the “world’s first atheistic state.” Both Islam and Christianity were forcefully excised from daily life during Enver Hoxha’s regime. Believers were imprisoned and religious leaders were hanged. Thousands of Albanians migrated to America that year to escape persecution, many settling in New York. One year later, Albanian immigrants in Flatbush began to congregate in the basements of churches, Arab mosques, and other public spaces. Finally, the community raised $122,000 to purchase this Victorian mansion in a neighborhood later designated as a historic district of Brooklyn in 1979.

The Brooklyn Ink

Imam Roland says that from the beginning, the mosque served not only as a place to practice religion, but as a cultural center for Albanians to rediscover their identity. Patriotism was palpable for these immigrants. They transformed their dismay over a homeland devastated by dictatorship into activism, in the form of demonstrations here in New York. The mosque’s first Imam, Isa Hoxha, had no formal religious education, “but he was a real patriot,” explains Imam Roland. Isa Hoxha had a saying, “There is no mother country without religion and there is no religion without a mother country.” Throughout the 70s, 80s, and until his death in 1997, Imam Hoxha strived to unite the Albanian community, regardless of faith.

Albanians who settled in America in the years after religion was banished were a devout group. However, their generation has since faded away. Imam Roland differentiates two kinds of Albanians that remain today. There are those of the Albanian diaspora, who escaped to Kosovo, Macedonia, and Montenegro early on, before coming to America. These people were able to continue practicing Islam freely in their temporarily adopted countries. When they moved to America, they brought religion with them.

But the Albanians who immigrated here after 1991, when the communist regime fell, never knew a different life than the one that had been forced upon them—devoid of their Muslim religion. And according to Imam Roland, they don’t experience the same desire to practice religion.

Imam Roland himself, meanwhile, is somewhat of an anomaly. The youngest of three siblings, his brother, sister, and parents worked at an ammunition factory in Poliçan while the Imam was still a child. Poliçan was an industrial city built around a factory that employed nearly 4,000 people. “In Albania, you were either a good working class communist, or you were against the regime,” he says. A 1966 government decree had ordered all citizens to change their names to “pure Albanian names,” so the distinction between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ was measured by whether or not an individual officially registered with the ruling party. Families like the Imam’s refused to do so and, as a result, were afforded almost no opportunities for a better life. They worked hard. “I remember, early in the morning, the noise of the factory. I can never forget it,” he says.

His parents were never educated in religion, though they still believed in God. The Imam recalls a singular moment when his father made reference to Islam. They were walking past an ancient mosque and his father pointed to a minaret exclaiming, “Roland, look! That’s where they did the call to prayer.”

The regime fell just in time for the Imam to attend high school. Muslim missionaries rushed into the country, hoping to revive what was lost. Imam Roland attended a madrassa run by Turkish Muslims. He later studied business administration in Ankara, and there he also attended weekly sermons. He arrived in New Jersey in 2007 and promptly earned a masters in public administration. He was highly regarded by the Imam of a New Jersey Albanian mosque, for his recitation of the Quran and his devoutness. Soon after, he was appointed to the mosque in Flatbush.

And he took up the task to revive it. “My motto is integration without assimilation,” says the Imam. He means that Albanian Muslims should participate in American culture and become the best in their professional careers, but not forget where they came from. He worries that Albanians are prone to assimilating to the point where religion is no longer practiced and traditions are no longer honored.

The Brooklyn Ink

Imam Roland introduced a youth initiative at the mosque one year ago, focused on the preservation of both culture and religion. He has organized a few events involving guest lectures at the mosque, usually by an Albanian English-speaking scholar, when possible. Sermons are followed by basketball games or arts and crafts. But the program hasn’t gained much steam. The Albanian American Islamic Center is governed by 10 board members, all of the older generation. Imam Roland says it’s been hard to communicate the importance of using resources to attract youth to people who get disturbed by kids running around the mosque. “Recent elections have resulted in a more open-minded board,” he says hopefully, his kids now clinging to both of his legs. Though still of the older generation, the new board turns out to be more persuadable regarding the youth initiative.

But young Albanians hold a different perspective. They tend to care more about their homeland than their homeland’s lost religion.

Dajana Alku, a Brooklyn College student, came to the U.S. with her family when she was 10 years old. She believes the government effectively erased any prospect of her practicing Islam. Dajana only knew a secular, democratic Albania. Still, she remembers her grandmother telling stories about government officials forcing people to drink water during Ramadan, to ensure they were not fasting. Extreme measures to remove religion ensured they would only identify strongly with their nationality. “There’s a very famous Albanian saying that goes Feja e shqiptarit eshte shqiptaria, which translates to “The religion of Albanians is Albanianism.” This had such a strong impact that even I, an Albanian born after the fall of communism, strongly identify with this saying,” says Dajana.

It appears that Imam Roland faces an uphill battle to salvage an Albanian identity that encompasses both Islam and culture. Flatbush was once home to a concentrated Albanian community. But throughout the decades, they’ve dispersed into other neighborhoods of Brooklyn. The Imam estimates about 50,000 people of Albanian ancestry live in Brooklyn. Though they exhibit strong ties to their homeland, it sometimes feels as though a comeback for the religion is a distant dream. How can he bring the mosque back to its beginnings, rooms brimming daily with worshippers?

Imam Roland emphasizes that his mosque functions as a cultural center first and foremost. Can a mosque that constitutionally requires all board members to be Albanian reach other groups that may influence religiosity of its community? In his answer, the Imam seems to suggest that this is not the plan. He seems unbothered that not many people outside Albanian circles know about his mosque. He who would rather not invite other groups, namely Tablighi Jamaat, whose missionary approach he deems “primitive.” Tablighi Jamaat is a nonpolitical group and many of its Bangladeshi and Pakistani members live in Flatbush, from which they travel from one mosque to another, passionately calling for unity among Muslims. “Albanians are not the most welcoming people,” says the Imam.

Leave a Reply