How parents are trading work for lower tuition and communal support at a cooperative preschool.

At 4 p.m. on a Wednesday afternoon, cubbyholes lining the hallway are still packed with lunchboxes, tiny backpacks, and the occasional stuffed toy. At a time when most preschools are closed for the day, the Park Slope Child Care Collective is open for business—and will remain open until evening.

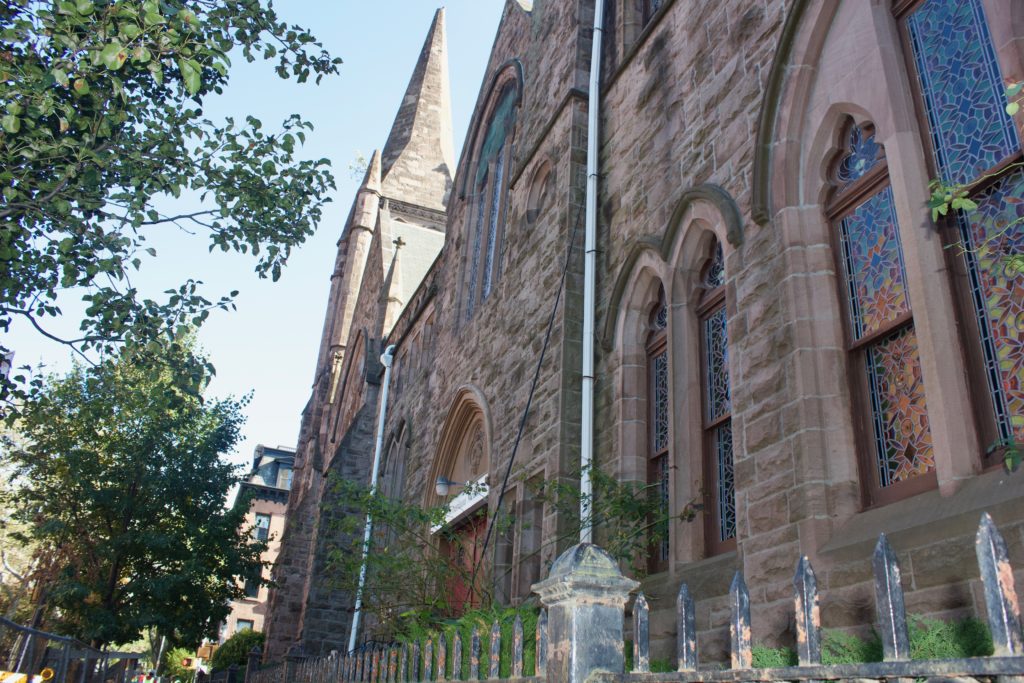

The cooperative preschool is just one example of the solutions parents are turning toward, not only to juggle work and family, but also to offset the heavy costs of childcare in America, even in relatively well-off neighborhoods like Park Slope. Nestled inside a church, the Collective was founded in 1971 by families to meet the needs of busy working parents. The longer 10-hour days, an 11-month school year, and fewer observed holidays provide flexibility not often found in other care centers, where the day typically ends before 3 p.m.

Other preschools offer after-hour care—at a price. Spending extra money isn’t something many parents can afford to do, especially with the ever-rising price of childcare. Nationwide, average childcare costs peaked at almost $9,000 per year in 2018, outpacing nearly all other expenses, according to Child Care Aware of America. In New York, parents spend around 14% of their income on care centers alone—double the 7% maximum that Child Care Aware recommends.

The Brooklyn Ink

Because many younger families move from other areas in the city to the famously family-friendly Park Slope, they don’t have extended family members nearby to help watch their kids. Working parents, like 41-year-old Tanya Ohly, instead have to rely on paid services like nannies or care centers. The Collective’s 8-to-6 schedule was a huge draw for her and her husband, both of whom work 11-hour days. They are among the approximately 97 percent of families at the preschool and 76 percent across Park Slope where all parents in the household work.

Traditional daycare centers are another option for working parents, but some find them lacking when compared to preschools. Linda Adamson, 42, chose to send both of her children to the Collective after a stint at a daycare center, which lacked the “educational component” she discovered in the Collective’s play-based curriculum. Although preschools tend to be more expensive than their daycare-only counterparts, Adamson found the “premium” of sending her kids to a more learning-focused preschool setting worth the approximately 15 percent increase in tuition.

The Collective and other co-op schools try to hold down costs that would otherwise be included in tuition by having parents take on jobs like repairs, cleaning, and fundraising. “We ask a lot of you, but you get a lot back,” said Jess Parsons, 41, who serves as a board member at the co-op and juggles three “crazy” kids, all of whom attended the preschool.

One of the “happy byproducts” that parents get out of the work system, which requires parents to fulfill 18 hours of credit per year, is the “loving and supportive” community it creates, according to Adamson.

Still, the tuition is not inexpensive, ranging from $17,000 to $26,000 a year, depending on the number of days per week attended and the child’s age. The Collective’s director, Martha Foote, explained that, when you spread the fee across the number of hours and days the center is open, parents pay less per hour than they would at other care centers. The Brooklyn Ink calculated the rate for a full 10-hour day at $10.03 per hour.

The Brooklyn Ink

Foote, a 57-year old education veteran with a gentle yet firm demeanor, works with her operations manager and the parent run school board to helm what seems to be a small, efficiently run ship, keeping a close eye on the annual budget. The team organizes the occasional fundraiser for things that are aspirational for the year, such as a ball pit in the gym for special needs children.

The Collective also hosts an annual gala to pool funds for financial aid. This year, it raised $30,000 to support around five families in need. The initiative is aimed at ensuring diversity in the classrooms across several factors. More than half of all students at the school come from families of color, are non-privileged socioeconomically, have non-traditional family makeups, or are children with special needs.

For Ohly, the preschool’s “universal values” of diversity and relative affordability were major factors in her decision to continue enrolling her children at the Collective, resisting seemingly attractive alternatives like Universal Pre-K. The city’s free public education program can come saddled with unexpected costs.

“Say I’m a working parent,” Foote hypothesized. “What do I do with my kids during school holidays and I have to work, or they get let out at 2:40 p.m. and I’m still at the office? I’d have to find a nanny or daycare center.”

These “after-school” costs are not as “cut and dry” as a one-time tuition would be, Foote explained. According to Park Slope Parents, an online community for neighborhood families, the average wage for nannies last year was $18.65 per hour for one child—a nearly 10 percent hike from the previous year. That doesn’t include other variable costs like overtime pay and paid vacations under the Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights, which took effect in New York in 2010.

The roughly $10 per hour cost at the Collective, plus dedicated teachers and the “peace of mind” of knowing her children are in capable and caring hands, are the driving reasons behind Ohly’s choice to keep her kids at the co-op preschool.

After covering teacher salaries, rent, and other related costs, the non-profit school doesn’t have much left in its pockets. “We’re looking to break even every year,” remarked Foote, who has served as director at the Collective for eight years. But, for teachers and parents alike, the communal support they find at the co-op school is more than worth it.

“It’s a precarious system,” said Parsons about childcare in the U.S. “We really need each other.”

Leave a Reply