New York City is one of America’s most diverse cities — but the same cannot be said of its public schools. Indeed, segregation along racial and financial lines has plagued the city’s school system for generations.

And public schools in Brooklyn are among the most significant examples of the problem, with two hundred of the city’s least diverse schools crowded into the borough alone, according to experts at New York University. “Segregation isn’t just about separating kids from each other — it’s separating them from resources and opportunities,” said Matt Gonzalez, a specialist on school integration and director of the Integration and Innovation Initiative at NYU’s Steinhardt School. “There’s a massive opportunity gap.”

Experts blame multiple factors. Among them are rising housing costs that keep lower-income families confined to school districts with fewer resources and admissions tests at some schools that favor wealthier students with greater access to test prep.

Lately, officials seem to be taking some steps to correct this. Mayor Bill De Blasio and the Department of Education have adopted dozens of pro-diversity proposals meant to boost diversity in the classroom. Plus, the mayor’s office has sent multiple school districts $200,000 grants to investigate how to put these proposals into action.

Meanwhile, one small startup school in Fort Greene has a plan of its own. In September, two Brooklyn teachers launched a junior high school on Lafayette Avenue called Brooklyn Independent, with a mission to make diversity central to everything they do.

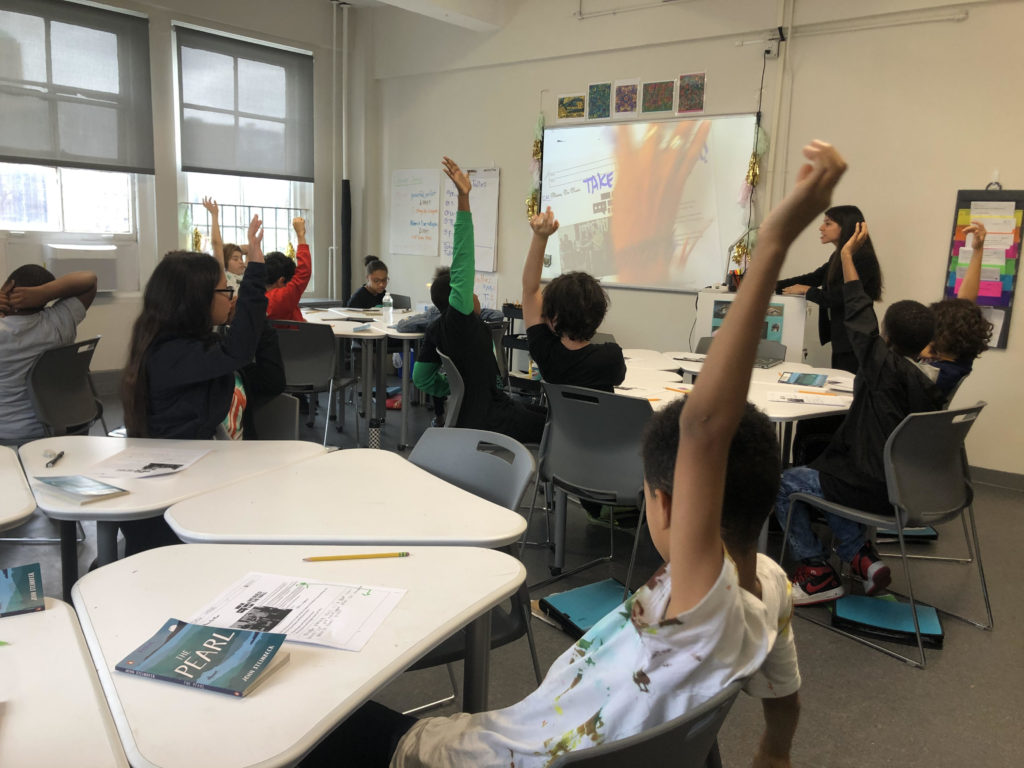

During a recent morning English class taught by Gabriela Tejedor, a humanities instructor and co-founder of the school, students debated themes from their assigned reading, John Steinbeck’s 1947 novel “The Pearl.” They compared key ideas from the book to a more current story: President Trump’s refrain to “build the wall” along America’s southern border.

Students’ hands shot into the air during the discussion; they had plenty to say.

The Brooklyn Ink

The lively and informed discourse in the class seemed fitting for a school which has made diversity its core tenet. Also worth noting — the sheer diversity of the students themselves.

The idea for the school, Tejedor explained, has been a few years in the making, since she and Kelsey Jones — her friend turned business partner — met at another charter school where they were both teachers. The ethnic homogeneity they saw in the classroom weighed on them, but the two educators shared a common, if radical, idea: Why not start a school of their own — one in which diversity would come first — to combat this?

Four years later, with the help of startup funding raised from friends, family members, and private donors, they made it happen.

It’s impossible to say how many students of each race the school has, because some students identify themselves as biracial. But next year, if all goes according to plan, the total number will rise from 19 to 60 as the school recruits about 40 additional pupils; by its fifth year, Brooklyn Independent’s student body should reach 150, according to the

co-founders’ projections. As they expand, they’ll bring on additional teaching staff, too.

The admissions process is simple: Prospective students take a math and reading diagnostic that tests their proficiency in core knowledge areas — “it’s not a sit-down SAT,” Jones said — and then their families join them for a meeting with the founders. In the meeting, the founders do their best to gauge “whether or not this is a good fit for families,” in terms of academics and their pro-diversity mission, Jones added.

They’re not seeking to collect as many prodigies as they can, Tejedor said. Instead, a student’s potential is what matters most.

The Brooklyn Ink

At the heart of the Brooklyn Independent’s diversity model is a sliding scale tuition system. Here’s how it works: Students’ families are divided into five income brackets, and one-fifth of the students are selected from each bracket. Families are charged tuition depending on their income; thus tuition can range from $500 per year on the low end, to more than $36,000 on the high end.

“To be quite frank, it’s the one option that ensures diversity across the socioeconomic spectrum,” Jones said. That socioeconomic diversity translates to multiracial diversity in the classroom.

Tejedor and Jones declined to disclose the specific number of families paying full tuition, but said the average is $12,000 per year.

Brooklyn Independent isn’t the first school to employ a sliding scale. Manhattan Country Day School, for example, a private high school on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, has been using the model for some time. But at that school, middle school tuition can surpass $50,000, dwarfing Brooklyn Independent’s cost.

Both Tejedor and Jones are new to the startup world. But they say teaching is their vocation and it feels right that this new venture, aimed at creating an inclusive, integrated space for students, has become their life’s mission.

The kids seem to be enjoying it, too, as The Brooklyn Ink observed on a recent visit. Every Friday, students go on field educational trips, such as a recent visit to the American Indian Museum, to learn more about

indigenous peoples in America; or the Museum of Natural History, to prepare for a geology lesson in science class.

Juggling all this can feel like a full plate, Tejedor said, but it’s worth it. “It’s a great feeling to feel tired, but so happy, because you love what you’re doing, building this from scratch,” she said. “This is our dream.”

Leave a Reply