The fluorescent lights of NF Lin Internet Cafe bled out onto Eighth Avenue in Sunset Park. Inside the cafe, rows of Chinese men stared at screens illuminated by video games, movies, and porn. It’s around midnight on a Wednesday in early October, the clacking of keyboards intensified and cigarette smoke enveloped the basement in a fog.

Tucked in a corner, a middle-aged man settled in for the night, a pillow wedged behind him and his few belongings scattered across the table—a pack of Marlboros and a red plastic bag of leftovers.

For many Chinese immigrants in Sunset Park, beds are hard to come by—but for $3 an hour, a worn black leather chair, a computer monitor, and a pair of noise canceling headphones become home for the night.

Resting one’s head on a table lit up by the glow of a desktop, however, isn’t unique to NF Lin Internet Cafe. It’s happening all along Eighth Avenue.

Aaron Jiang, a 40-year-old immigrant from the Guangdong province in southern China, opened Ohiyo I-Cafe, an internet cafe, a decade ago. For $2.50 an hour for non-members and less than $1 an hour for members who paid a one-time $25 fee, customers could come to the cafe after a long day of work to unwind for hours side-by-side. Jiang said his customers, mostly men, were often “playing games and falling asleep.”

The competition forced Jiang to close the cafe in 2016, as more and more internet cafes cropped up along Eighth Avenue. Ohiyo I-Cafe wasn’t bringing in enough money, which ultimately led Jiang’s business partner to pull out of the business agreement.

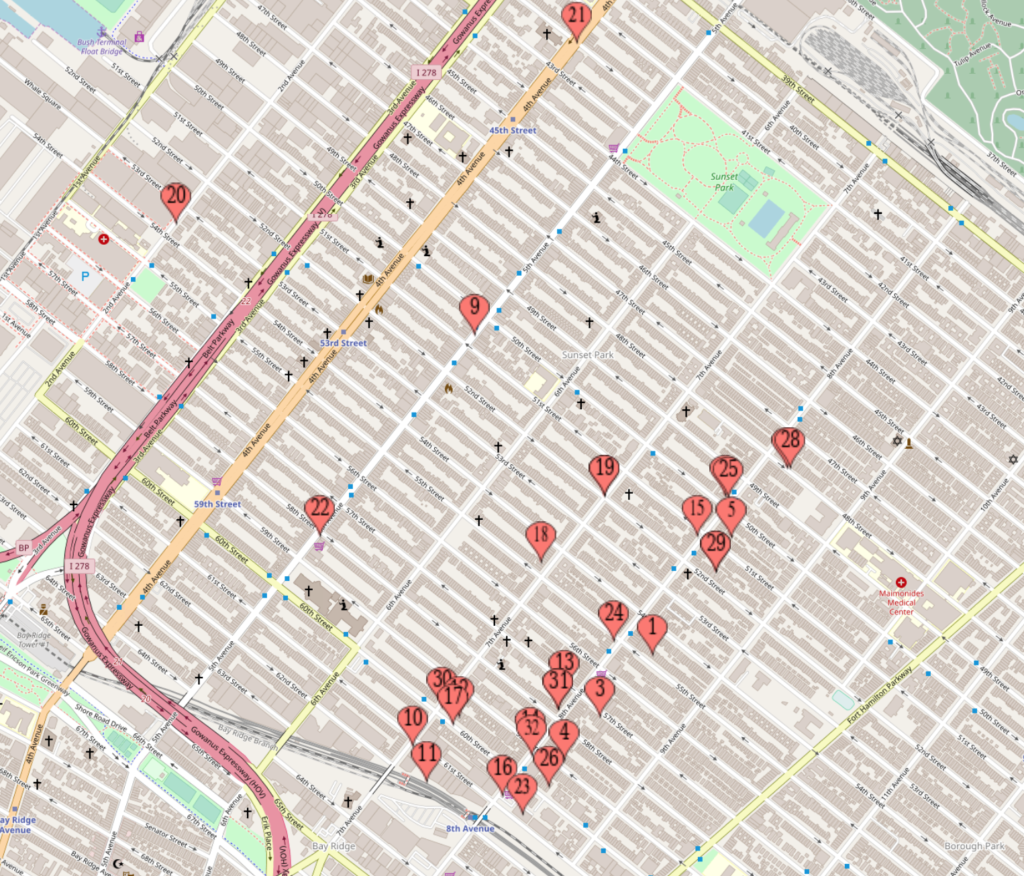

There are at least 32 Internet cafes in Sunset Park, 18 of which are along Eighth Avenue. However, the exact number is likely much higher, as there are cafes operating illegally.

But Internet cafes didn’t become an unofficial shelter for working-class Chinese immigrants because of comfortable chairs or high-speed Internet access. They became a temporary refuge out of necessity in the midst of a high-cost housing market—and a desire to belong within the rapidly growing neighborhood, as well as beyond its perimeter.

For decades, thousands of immigrants—both documented and undocumented—have made the long and expensive 7,000-mile journey from China to New York only to find themselves working labor-intensive 14 to 16 hour days for little pay, often as factory workers or home attendants.

As Manhattan’s Chinatown grew crowded with immigrants from mainland China in the 1980s, many Fuzhounese followed the N and R subway line down to Sunset Park where they found space and opportunity along the abandoned commercial section of Eighth Avenue. In Chinese culture, the number eight represents prosperity and success because its pronunciation in Chinese, ‘Ba,’ sounds similar to ‘Fa,’ meaning wealth or fortune.

“To the Chinese, Eighth Avenue was a golden opportunity,” said Paul Mak, founder of the Brooklyn Chinese-American Association. “It served as an opportunity for people to come to a new community with the affordability and space to follow their dreams.”

Recent immigrants who didn’t know English knew which stop to get off because the Eighth Avenue station was the first stop in Brooklyn above ground. The Chinese community came to refer to this station as “blue sky” station because of the daylight that illuminated the dim subway car as it slowly emerged from its underground tunnel, Mak said.

Sunset Park is now the largest Chinatown in all five boroughs of New York City. According to the 2018 U.S. Census Bureau, 29 percent of Sunset Park residents are Asian. American Community Survey 2017 5-year data shows 44 percent of Sunset Park residents are foreign born—51 percent of the foreign-born population is from Asia, 49 percent of which are Chinese.

Internet cafes are popular in Asia, where they originated, so it’s unsurprising that they are found on nearly every block in Brooklyn’s Chinatown. Internet cafes, or more commonly seen in neon lights along Eighth Avenue as “網吧” (pronounced ‘wǎngbā’), are small spaces, which provide high-speed Internet access to the public for a small time-based rate of around $2 to $3 per hour. Many are open 24 hours a day.

On a recent night in Sunset Park, the cybercafes were primarily inhabited by working-class youth, but as day turned to night, more and more middle-age men filled the empty chairs between gamers. Women were rarely seen in these spaces.

“Most of those staying overnight in the Internet cafes have no housing or family,” Mak said. “Some of these people have no other way of living.”

Many of the single men taking shelter in these cafes most likely work out of state five to six days a week and return back to a familiar community for a day of rest, Mak said. A small cafe with desktops, a bathroom, and the occasional shower facility becomes a refuge for many of these men.

Despite an “open door policy,” these 24-hour cafes rarely welcome outsiders. Even a reporter, willing to pay for a seat, was turned away from several establishments under the guise of “we are closed,” in broken English (despite visibly full rooms of over 20 Chinese men sitting in front of desktops). But also those from within the Chinese community who are from a different province than those in the majority at a given cafe can be considered an “outsider.”

Each internet cafe maintains its own “geographical and linguistic allegiances, as people from the same part of China speaking the same dialect, some of them friends, are drawn to a particular cafe and claim it as their own,” writes Sarah Wendolyn Williams in her 2013 dissertation, “The Digital Diaspora in Sunset Park: Information and Communication Technologies in Brooklyn’s Chinatown.”

These allegiances extend far beyond cafe walls. Steve Mei, the Director of Brooklyn Community Services at the Chinese-American Planning Council, sometimes felt excluded among those speaking other dialects as an immigrant from Guangzhou to New York in the 1980s.

“You look the same, but you come from different worlds because you speak with [different] dialects,” he said. “Some folks tend to think that the Fuzhounese are more aggressive or some folks tend to think that Cantonese have been in the country a little longer than other folks may be.”

What Mei refers to as an “internal stigma” in the Chinese community plays out in such a way that even within an immigrant community, people who speak the same dialects find a sense of home among those most similar to them.

Mon Yuck Yu, the executive vice president and chief of staff of the Academy of Medical & Public Health Services sees this in her work with Chinese immigrants everyday. The Academy of Medical & Public Health Services is a non-profit health service organization that provides social assistance to underserved immigrant communities. She affectionately refers to these individuals as “community members” to build intimacy and trust between one another; she herself is the daughter of immigrants from Guangzhou.

Yu said that social spaces like karaoke bars and internet cafes are “really a way for [immigrants] to build that network, especially when you’re coming into a community like Sunset Park, where most of everyone is Chinese speaking, but you don’t really have anybody who you know.”

While language can be a barrier within the Sunset Park community, Yu realized it is also a barrier between this community and broader non-Chinese information and services. Yu found herself on the frontlines of the tuberculosis outbreak, which first flared up in 2013 and again in 2015.

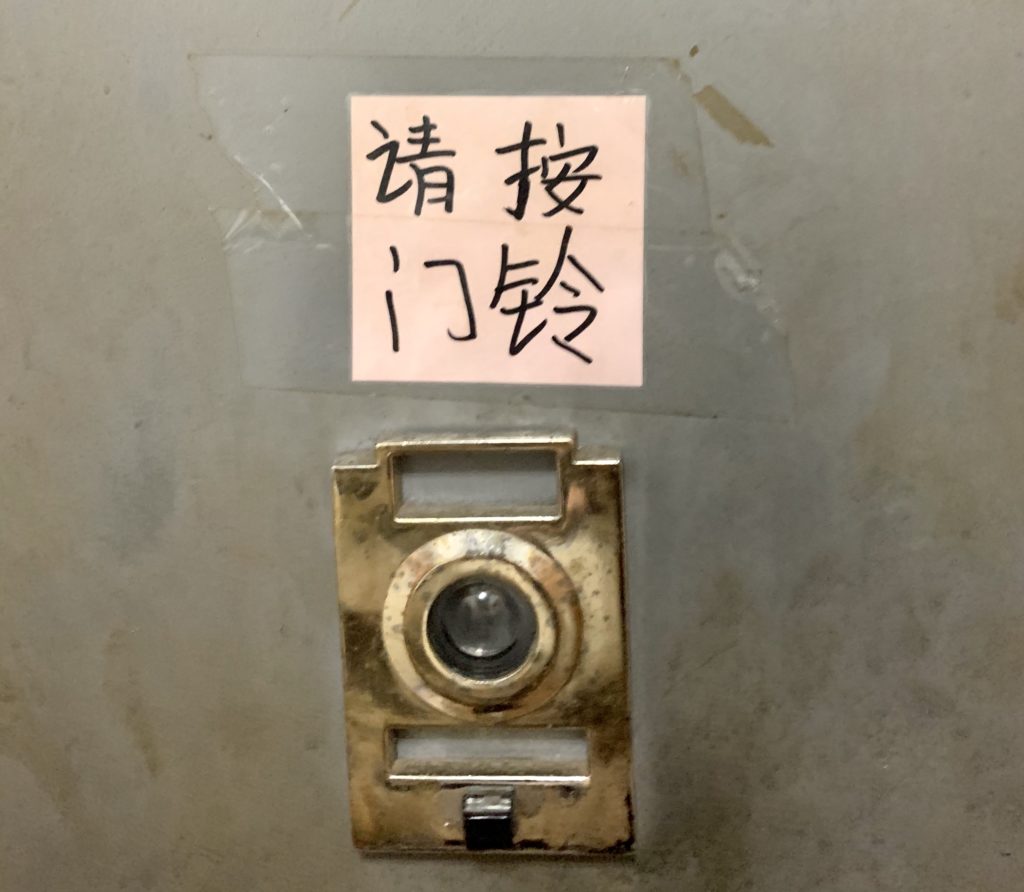

The disease disproportionately affected Chinese immigrants in the community, many of whom were young men who worked out-of-state and frequented enclosed spaces like Internet cafes. While some Internet cafes appear well-regulated and clean, other spaces are very enclosed, dark, and filled with cigarette smoke. Many of these poorly ventilated cafes can be found in basements or within home-based establishments only identifiable, for example, by a small sticky note on a closed apartment door that reads in Chinese, “Please ring the doorbell.”

Very few cafe owners were aware of the TB outbreak because many of the primary outlets covering the epidemic were only in English. In an effort to raise awareness among Internet cafe owners, Yu traveled from cafe to cafe to ensure owners were taking the proper measures to address their employees’ and customers’ health. She also took to WeChat, a popular Chinese social media app, to spread the word about the disease and where to receive free treatment. Yu was struck by how these structural and social barriers prevent Chinese immigrants from accessing the various services they are entitled to from healthcare to housing to education.

The keyword here is access. For this population, access cannot be granted without knowledge of one’s rights, and one’s rights are almost impossible to ask for—or even comprehend—without understanding a word of English.

And one of those most significant rights is housing. Immigrant populations are particularly vulnerable to unsafe housing conditions, severe crowding rates, and tenant abuse.

Yu recalled an 80-year-old man whose calligraphy artwork decorates the walls of the Academy of Medical & Public Health Services. His living arrangement in Sunset Park was a severely overcrowded space with a shared kitchen and bathroom where he endured countless incidents of theft and discrimination from other tenants. He was recently granted affordable senior housing—in Harlem, leaving him with a disconcerting choice: to remain in unsafe living conditions, or to leave his community with its familiar daily fish markets and inexpensive bundles of longan fruit.

The NYU Furman Center defines a severely crowded household as “one in which there are more than 1.5 household members for each room (excluding bathrooms) in the unit.” In 2017, 9.1 percent of renter households in Sunset Park experienced a severe crowding rate, the fourth highest crowding rate of all New York City neighborhoods.

This is in part due to housing discrimination. Under NYC Human Rights Law, it is illegal for landlords to discriminate against tenants based on identifiers such as citizenship status, national origin, or race. Still, Yu said, housing is hard for people in the community to come by, and both she and Mei have consistently seen both documented and undocumented residents denied access into housing facilities.

“You have a lot of folks, around 10 to 12 people, who are cramming themselves into apartments meant for four or five people,” Mei said. “There’s the fear that ‘if I can’t live here, where am I going to live?’”

These are the circumstances that often give many Chinese immigrants no choice but to be lulled to sleep by the clacking of keys and the buzz of neon lights. The situation is not ideal, but for many, the alternatives are even worse. These cafes can provide a space for those who may need a night away from a crowded room, or a place to lay their head between shifts.

The cigarette smoke becomes a warm blanket after a grueling 16-hour day, the consistent keyboard strokes begin to sound like a lullaby. Calloused hands fold neatly onto one’s chest, tired eyes close, and for a couple hours one may drift away.

Leave a Reply