She loved her.

Reverend Aimèe Simpierre conjured memories of her childhood love during our first phone call. She spoke slowly, “I used to draw pictures of her eyes and mouth in class.” Reverend Simpierre went silent after that. She called this love spiritual; she remembered wanting to be just like this woman, but also loving her. This childhood love was her “spiritual mom” and mentor. They haven’t spoken in years and Simpierre supposes much like other old friends and church family, the reason is that she heard Simpierre was gay. Either that or she was no longer alive.

There’s a delicate and difficult balance to being Black, gay, and Christian. And Reverend Simpierre’s story is about tipping the scales.

Simpierre is now the acting pastor at The Potter’s House: Church of the Living God, a Black- and LGBT-founded, non-denominational church with a predominantly gay congregation.

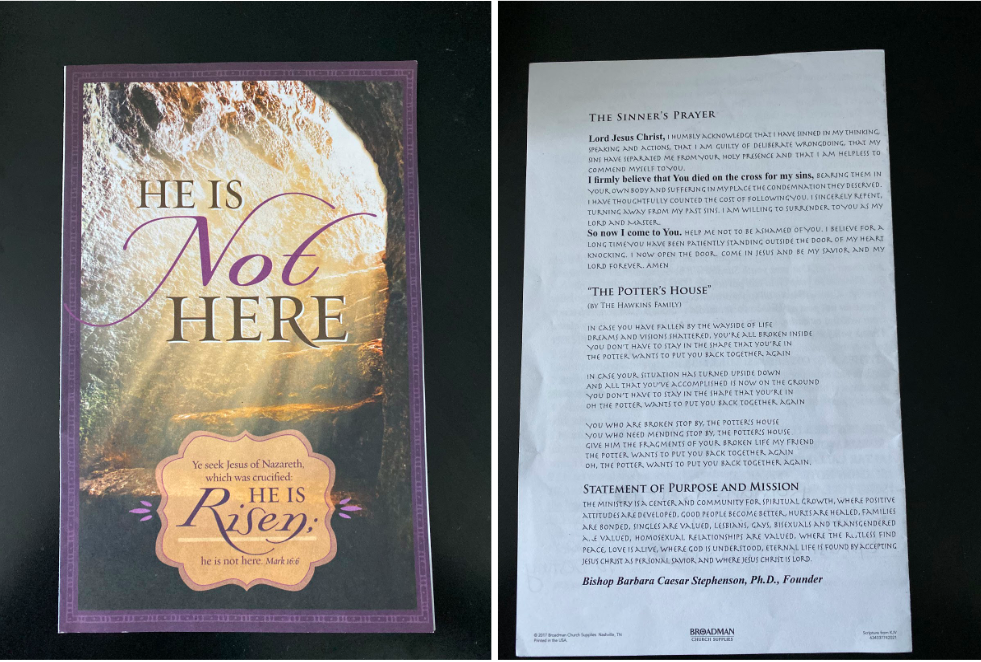

Black LGBT people in the Bedford-Stuyvesant community and beyond come to the Potter’s House to witness the church’s mission statement in action. Written by the founder, Bishop Barbara Caesar-Stephenson, the statement of purpose can be found on the back of every bulletin and on their website welcoming all races, identities, and other demographics. In it, the church vows to be a place of healing and peace.

From the pulpit of the small sanctuary, Simpierre preaches to congregants that have been ostracized and abandoned by their home churches and families. Some have been abused. Others are still fearful they’ve been condemned by God. They all are familiar with a story like the one Simpierre told me: a Black church has isolated them.

Chapter I. A Fish In The Sea

When Simpierre first came to The Potter’s House with her partner Myriam in 1999, who now leads services with her at the church, her understanding of her spiritual journey began to change.

She was born into an atypical religious dynamic: her mother was a Quaker and her grandfather was a reverend at the famous interdenominational Riverside Church in Harlem, while Simpierre was raised in various Protestant churches. For a few years, her mother identified as Pentecostal, then Apostolic Pentecostal, before converting back to being Quaker. Simpierre considers those years some of the most formative in her early spiritual journey. Her home church was Greater Refuge Temple, a predominantly Black, Apostolic Pentecostal Church in Central Harlem. There she developed the gift of speaking in “tongues” at age 14 and became a witness to the power of God for those around her.

“A kiss leads to premarital sex, which leads to hell,” Simpierre said as she repeated the basic tenants of sexuality in the Church. At the time, Simpierre had no sense of her own sexuality. She remembers accepting the indoctrination so completely, especially when it came to God’s feelings toward gay people. “I don’t even remember being taught this per se, but I just knew instinctively that if I came across a gay person, I had to let them know that God didn’t love that,” she said. Simpierre believed it was her responsibility, even though something about it didn’t sit right with her.

In 1991, Simpierre was still a student at Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts when she was witnessing to one of her classmates, a friend who also lived in her grandmother’s apartment building. The two of them frequently took the bus to and from school together, when one day he asked her if it was okay to be gay. She repeated what she was taught and firmly told him, “No, it’s not.” The two grew distant by the time they went to college.

Ten years later, she bumped into him again on a bus ride in a nearby neighborhood. “The first thing I said to him was it is okay. And that I go to a gay church now and here it is,” she tells.

This friend, Morgan Varona, now sits in her congregation at The Potter’s House as she preaches a new doctrine: God still loves gay people.

“It immediately felt very familiar and very warm. And I just sort of knew right then and there that I belonged,” Morgan said about his first few visits to the Potter’s House. “What I love about the Potter’s House is that although most of us are LGBT, it’s not like some big gay party. It’s actually church. It’s Bible based and Christ is in the center of it all,” he said, laughing.

Before he encountered Potter House, going to church was not comfortable, he said. “It’s like every time I would get to a certain point somebody would say something about homosexuals and condemning gay people. And it was just awful,” he says. He described being Christian as something he felt in his bones; a trait he was born with in the same way that he was born gay. The Potter’s House was a place of refuge where being gay and having a loving relationship with God didn’t feel irreconcilable.

During his time at the Potter’s House and with Simpierre’s guiding hand, a single word echoed throughout over a decade of memories, “Free.”

Chapter II. To Freedom

Before attending undergrad at Barnard College in New York City in 1994, Simpierre left Greater Refuge Temple and her relationship with God. She made it clear that God did not leave her, but rather she left Him and the organized religion she felt had misguided and eventually, mistreated her. She also still had no understanding of her sexuality. Choosing an all-girls school for college wasn’t something Simpierre had worried about, having attended an all-girls junior high school before.

“People would always say to me, ‘Oh, you go to an all-girls college?’ And then it started to dawn on me: I had never missed guys because I just wasn’t attracted to them,” she said.

However, the woman Simpierre would fall in love with and eventually marry did not even attend Barnard.

Simpierre met Myriam in New York in July of 1995. The two would often talk about their spiritual beliefs as Myriam prepared to be initiated as a Voudou Priestess in Haiti in September of the same year. Myriam, a proud Haitian woman, was also raised in Black churches and attended Catholic schools in her childhood. Both of Myriam’s parents were leaders in their Gnostic church and her family often identified with Catholicism since it is the predominant religion in Haiti. Her mother also dabbled in spiritualism.

“My first gift to her was a Bible,” Simpierre says. The two began a journey of finding God on their own and defining how He felt about their relationship. Myriam had a two-fold challenge when it came to her journey: she realized that practicing Voudou and spiritualism was not her calling so she would have to reconcile with God, and she also faced the homophobia prevalent in her Caribbean family.

“It was only difficult when I was around my mom or just being around my parents,” Myriam said of being openly gay. “For her, it was more of a ‘hush-hush’ in terms of what friends or what people know about it.”

Her mother chose not to attend her and Simpierre’s commitment ceremony on May 4, 2002. Now, she and her mother have come to an understanding. “If she had to visit my church or see my friends, it wouldn’t be a problem. I think it’s just the other way around,” she said of being around her mother’s circles. Myriam paused as she recalled her mother visiting The Potter’s House a few years ago. She believes her mother had a good experience.

Chapter III. The Altar Call

Simpierre can’t remember what Pastor Stephenson preached about when she first encountered her.

It was 1998, and Pastor Stephenson was an assistant pastor at the Unity Fellowship Church in Brooklyn. The Unity Fellowship Church Movement was founded in 1982 by the Reverend Carl Bean in Los Angeles, California. Bean wanted to found his own Black gay church so that Black people of any sexual orientation and denomination could worship God— without judgment in the Black church and racism found in the predominantly white LGBT churches. Bean also had an important social justice mission, the Minority AIDS Project, to make up for the Black church’s slow response to the growing AIDS epidemic permeating the Black community. The movement expanded across the country, including New York City.

At the time, the Unity Fellowship Church of New York City was sharing space with St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn. The Sunday that Simpierre and Myriam attended in 1998, Pastor Stephenson was preaching in the absence of Pastor Elder Zachariah Jones. Simpierre can’t remember what the sermon was about, but she remembered getting up for the altar call. “I waited until the very last minute then I snuck on the back of the line. And you know what the spirit of God did when she laid hands on me? It reawakened me, my life, my calling, my relationship with God.”

Chapter IV. The Written Word

Reverend Simpierre attended Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism from 1998 to 1999 and wrote a Masters thesis entitled, “Whosoever Will, Let Him Come: The Rise of the Black Gay Church.” It now sits tucked away on the high bookshelves of Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs Library. It joins thousands of other Masters theses published before 2015, bound in soft green covers.

In her writing, Simpierre chronicles the beginnings of The Potter’s House: Church of the Living God. Founded in the basement of a brownstone on the corner of Halsey Street and Marcus Garvey Boulevard, Pastor Stephenson and the founding members wanted to do something Unity was not comfortable doing. They wanted to minister about Jesus.

Stephenson was raised in a Black church called Mount Calvary Holiness Church, according to Simpierre’s thesis. She began preaching at age 12 and was ordained at 15 years old. Stephenson had been married for two and a half years when she divorced her husband at 22 years old and chose to come out to her congregation. Thinking that she would be accepted by her church family and allowed to continue preaching, Stephenson told them she was a lesbian. Not only did they not accept her, but she was shunned and ostracized by any closeted members she was friends with. Stephenson would stop preaching until she came to Unity in 1993. Again, she was met with conflict when she practiced the traditional “laying of hands” on the congregation, something normal in Baptist and Pentecostal services.

Pastor Stephenson and other like-minded individuals wanted that authentic gospel feeling to their church experience.

After attending that first service at Unity with Myriam in 1998, Simpierre began attending that church regularly. The service which Stephenson had preached reminded her of the church experience she was used to. She encountered an old friend who had also grown up at her home church in Harlem and was preparing to become Pastor Stephenson’s assistant at her new church.

Simpierre remembered, “He saw me and kind of took me by the shoulder and said, ‘Aimèe, I know you like Pastor Stephenson, she preaches like what we grew up with. You know, you need to follow her and go to her church. She’s starting a new one and here’s where it is.’”

Chapter V. Singing Psalms

It began with a song.

Simpierre and Myriam had met because of their love for music; both played instruments and played in Simpierre’s band, Rhythm of Aqua. It only made sense for them to take over the musical component to The Potter’s House services. Myriam played the drums and Simpierre sang and played the organ while leading praise and worship. Recognizing their anointing, Pastor Stephenson took them both under her wing. Simpierre spent all her spare time with her, learning and being trained to lead a flock of her own. Stephenson pushed her to attend many Bible and preaching classes, making sure that her education was thorough without formal seminary training.

Since the church is non-denominational, which means there is no oversight body, there is no certain amount of requirements necessary to be ordained. Still, for years, Simpierre studied. She was ordained in a Sunday service on October 9, 2011.

“Somewhere along the line I realized that God still loved me, and this great baptism I had, speaking in tongues at 14, was still there,” Simpierre said. “He didn’t snatch it away from me when I realized I was gay.”

Now that she leads others who also struggled with this realization, she feels protective over their journey back to God and the new relationship some are fostering with Him.

Chapter VI. The Judgement

Simpierre now preaches about the injustice that religious indoctrination has supported when it comes to the Black community. “It grieves me that the Black church has seen how scriptures have been used to oppress people for so long, but doesn’t recognize the pattern when it comes to the LGBT community,” Simpierre says, referring to the Biblical scriptures used to justify enslaving Black people for hundreds of years.

Simpierre believes it’s time for the Black church to look at how these scriptures have been interpreted. This may be true since the word “homosexual” was added to the Bible for the first time in 1946. It appeared in 1 Corinthians 6:9-10 in the Revised Standard Version and other verses throughout the Bible. The word was translated from a combination of Greek words malakoi and arsenokoitai, which can be translated to “boy child molester.” If Bible scholars were to revisit this translation, then this would change the interpretation of many, but not all, scriptures used to condemn the gay community.

In a sermon, live-streamed on The Potter’s House Facebook page, Simpierre preaches about the indoctrination that slaves had to endure. They were taught that God had cursed them and meant to keep them in bondage. Harriet Tubman, revered as the “Moses” of her people, didn’t believe this was the God who had also freed the Israelites. She had to shake that indoctrination and find freedom, trusting that this was really what God intended for her.

Tubman was a part of a bigger trend. In history, the Black Christian faith had inspired slaves and was often used to escape oppression. Negro spirituals were used to teach escape plans and bring hope to slaves, secret Bible studies occurred under the cloak of night, and unsupervised worship services were held by slaves on some plantations.

The Black church, regardless of denomination, became a pillar in various Black communities once these slaves were freed. Over time they became cultural hubs and central spaces to address grievances and plan movements of social activism, especially during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Now, history seems to repeat itself, with the continual emergence of Black gay churches redefining who God says is condemned.

Dr. Elijah G. Ward is a former professor at Saint Xavier University and is an expert in sociology, anthropology, and black studies. In his 2005 research article, “Homophobia, Hypermasculinity, and the U.S. Black Church,” he examines homophobia in the powerful institution of the Black Church as a harrowing aftereffect of slavery.

This analysis still echoes the prevalent homophobia occurring in the Black community, Ward said, adding during an interview, “Black people, in bondage and even out of bondage, have a need to be accepted by America, by middle-class society, to be accepted in the white community.”

Ward continued, “Because of the history of sexual exploitation in slavery and the deep psychological pain that caused black people, they didn’t want to be vulnerable to the attacks of white people saying they were deviant sexually.”

Even though now the Black community won’t consciously say they need to be accepted by white America, there’s a generational pain there that has caused this homophobia to be ingrained and accepted. This homophobia isn’t just because they want a greater community to accept them, but now they seek acceptance from other Black people. To be gay is a betrayal, and to accept a gay Black person is a bigger one. That Black people know their history of oppression and still perpetuate stigma about another group is evidence of anxiety about perception and acceptance.

“This culture is like fish in the sea. They don’t notice the water because they’re surrounded by it,” Ward said.

As Simpierre, Myriam and I ended our last interview, we spoke about the visitors who come through The Potter’s House.

Simpierre speaks in hushed tones as they’ve just put their two small children to bed in the other room. “We’ve had folks just kind of wandering in off of the street because they’ve heard the praise and worship happening and were like ‘Oh, it’s a good church!’” she said. “Then they come in and start to look around. See how people are dressed. You can see them just start slowly backing out.” Yet, many visitors stay and enjoy the Potter’s House services.

They’ve even had a visitor who identified as an Evangelical prophet that testified one Sunday and was invited back by Pastor Stephenson. “You could tell she was fixing her mouth to say something about gay folks,” Simpierre said, retelling how the woman talked in circles and grappled with that unassigned Christian duty to condemn them for what they were doing.

Reverend Simpierre takes time to delete hateful comments and messages from The Potter’s House social media, a lot of them from other Black traditional churchgoers. Twenty years later, people are still drawn to the atmosphere of The Potter’s House, but they can’t seem to reconcile that God might just love the “condemned.”

Leave a Reply