For Mr. Ichiro Kato, a 71-year-old woodworker who lives on President Street, Carrol Gardens, transportation is a daily struggle. The closest subway station, on Carroll Street, is 10 blocks away from his home, and to go to his workplace in Long Island he must drive. The worst part is the trip back home. “It is a nightmare every day,” he says.

For people travelling to Red Hook, a neighborhood five blocks south of Mr. Kato’s home, past the Expressway, lack of public transportation is even worse. Akiko Uchida, a 29-year-old Japanese designer, has ventured few times into the isolated zone. She usually takes a shuttle to get to her destination, which is always the same: the IKEA designer furniture store, located at the waterfront, on Red Hook’s southern edge. The shuttle is free for customers who come to pick up an order—the Swedish company’s response to the poor transportation system. Recently, though, Ms. Uchida decided to take the B-61, one of two bus routes that pass through.

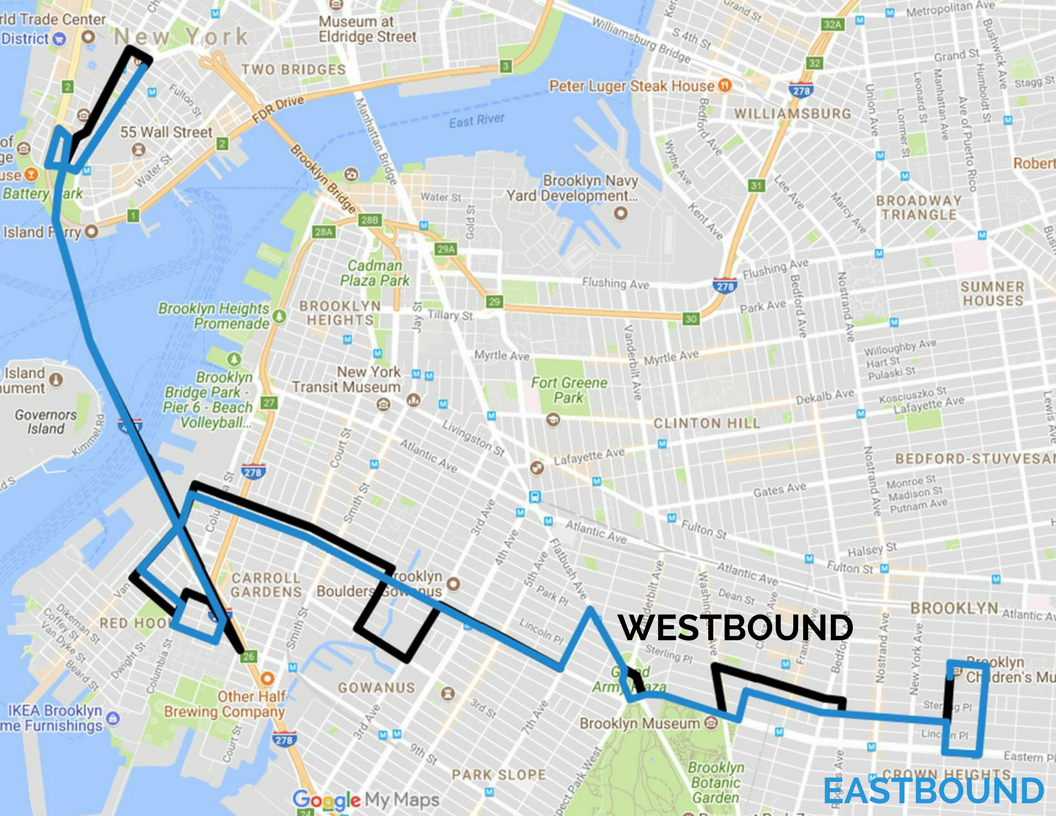

Council Member Brad Lander has described Red hook as a “transit desert,” with no bus or subway routes up to a mile in two different directions. On Monday, November 13th, a coalition of elected officials, community leaders, cultural institutions, and neighbors handed a petition with 2,500 signatures to the MTA Transit and Bus Committee, asking to bring back the B-71 bus route. The proposal calls for an expansion of the route, in fact, that would link Crown Heights with lower Manhattan, after traveling through Red Hook.

With no deadline for the MTA to reach a decision, the process of reopening the route could take many months. “We don´t have an exact timeline,” said Whitney Hu, the Chief of Staff for Lander. She expects the process, however, to be quicker than the opening of line B-37, which took about two years. Adding the link to Red Hook and Manhattan, a suggestion from the MTA made two years ago when another initiative for the B-71 failed, will make a stronger case for the new B-71+, as it is now being called, she said.

However, what lies in the minds of the MTA’s Transit and Bus Committee is still a mystery. Its members have made no public statements. Stephanie Wilchfort, the president of Brooklyn’s Children Museum, attended the Transport and Bus Committee meeting on Monday 13th , but she explained that it was just a hearing and there was no forth and back conversation. She also said that she would continue to “stand with the coalition of supporters” of the bus line.

The Children’s Museum would be a stop on the proposed B-71+ line. So would the Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Museum, and Botanic Garden. Such possibilities motivate parents like Kathy Park Price. In the press release issued by the coalition after the hearing, she recalled a personal experience that pointed to the impact the route could have in the daily lives of Brooklynites.

“Last week, I timed a trip that I’ve been reluctant to take because I knew it wouldn’t be fun; it’s a 3-mile distance that would take 15 minutes on the B71. Getting from Park Slope to the Brooklyn Children’s Museum in Crown Heights can take, surprisingly, an hour by public transit and it did when l went last week.”

Others invested in getting back the bus that once took them to their doctors are the seniors that frequent the Amico Senior Center. Carrol Reed, the director, said that many of the seniors go to see doctors on Union Street, a stop that was covered by the old B-71. They used to take the bus, but now “they have to take a car service and it is expensive,” she said. For seniors, buses are usually a great option, because unlike subways they require taking no stairs.

This is exactly what bus advocate Bill Raudenbush stresses the most. “Buses are all about mobility,” he said. “You can’t go anywhere on a subway, because you can’t get down the stairs.” Even the stations that do have elevators, they’re often broken down. People he knows who are not very mobile, he says, “don’t take the subway, they take buses”.

In Radenbush’s opinion, successfully advocating for a bus line takes three main things: “Time, grassroots, but most importantly, political pressure.” But he does give “credit to the MTA for having very public and open board meetings,” that allow for important advocacy.

Leave a Reply