The flow of voters at P.S. 120 on Beaver St. in Bushwick was slow around 1:30 p.m. on election day, but that didn’t worry Erdyce Romeo, a poll worker and a JFK Airport employee. As she checked in voters that afternoon in the elementary school gym, she savored a break in voter traffic. Things were already going better than expected.

“It’s been a great turnout,” said Romeo, 35, who had been checking off registered voters in her thick booklet since 6 a.m. that morning. “A lot of people here are still on their first booklet. We’re on our fourth.”

A five-minute walk away, at the 50 Humboldt St. polling site, poll coordinator Aeshia Williams, 46, also was busy. She happily announced that 232 Bushwick residents had cast their votes by 2:30 p.m. “This is a good turnout for not a big election,” Williams said.

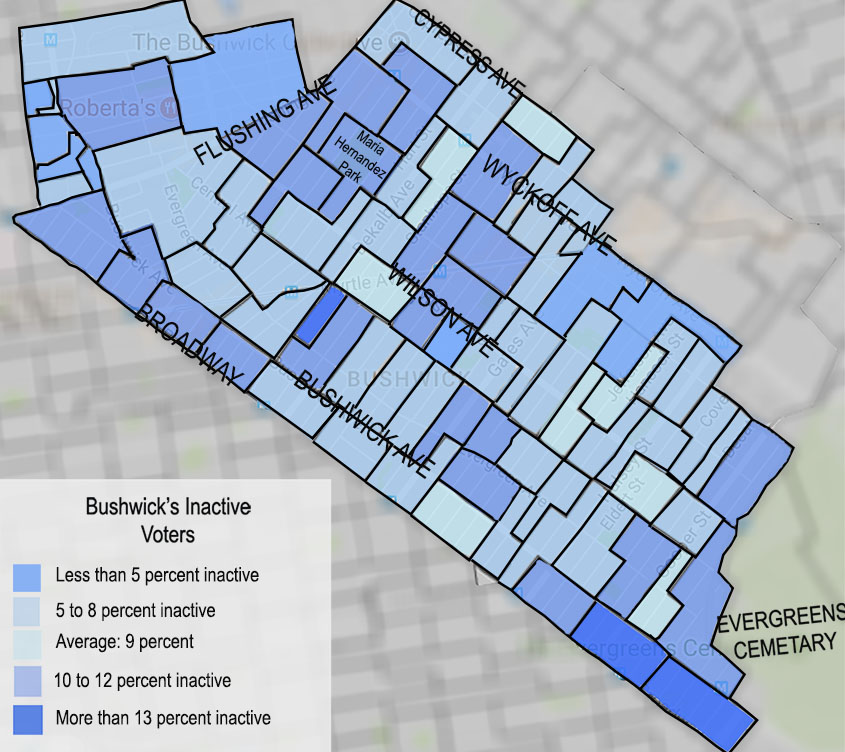

But though both were relatively busy this past election day, the polling sites at P.S. 120 and 50 Humboldt street—only five blocks away from one another—are in separate worlds when it comes to percentages of inactive voters, according to analysis of Board of Elections (BOE) voter registration data. While the Humboldt St. site is one of the more politically active districts in all of Bushwick, the site at P.S. 120 has an above average percentage of inactive voters.

One reason for the disparity? The pace of neighborhood change on both blocks. While 50 Humboldt St. has seen little development over the past five years—it primarily serves a housing project built in 1960—P.S. 120 sits on the edge of Bushwick’s rapidly revitalizing commercial district. Rapid change, it seems, disrupts voting patterns.

The streets outside the P.S. 120 polling station are home to several new businesses, and two hotels. Nearby, for-lease signs sit atop buildings as even more new tenants flock to the neighborhood. Inside the polling station, 40-year poll inspector Delores Jamison, 73, has noticed a shift in the demographics that show up to cast their votes. In the P.S. 120 election district, 12 percent of voters are registered as inactive—meaning they died, moved away, or didn’t participate in the past two federal elections.

“With the new condos there are new people coming in, but most of the people who went to school here moved away and now live somewhere else,” she said.

Experts on urban policy and election politics have said that gentrification and voter turnout are linked. A study done by researchers H. Gibbs Notts of Western Carolina University and Moshe Haspel of Spelman College found that voter turnout plummeted by as much as 20 percent in Atlanta’s highly gentrified neighborhoods.

“Participation will lag among new residents lacking community connections,” the researchers wrote in Social Science Quarterly. “Studies have also demonstrated that ‘people who talk together vote together.’”

When old-time community members leave, their investment in local politics leaves with them. Jamison noticed it herself at the P.S. 120 polling station—she doesn’t see the same faces she saw 40 years ago.

“Now the area is more built up, and the people who were here are moving out,” Jamison said. “I wonder what happened to the older people…the ones where you know their names and families.”

It’s a different story down at the 50 Humboldt St. polling site, where coordinator Aeshia Williams, 46, has been working since she was 18. She knows the names and faces of the people who stop by to vote, many of them residents at the Bushwick Houses, a housing project attached to the polling site.

In her election district, only five percent of voters are registered as inactive.

“This is the site for the projects, and we get mostly older people,” Williams said. “I also try to get younger people involved.”

Williams remembers when her mother worked the polling stations at 50 Humboldt, for $86 a day. Since then, there has been little resident turnover at this polling site. Williams herself has been living at the Bushwick Houses since she was three.

Williams also encourages residents at the Bushwick houses to take the six-hour course to become a poll worker. The pay is good, she says, and it keeps people involved with local politics. She has amassed a dedicated crew of six poll workers who have been working election days for several years.

As lifelong Bushwick residents, many of the tenants at the Bushwick houses have a high stake in local governance. And it shows it their voter registration data: Both districts have about 1,000 members, but 50 Humboldt has 69 fewer inactive voters than P.S. 120’s district. That’s a roughly seven percentage point difference.

While the BOE data paints two different pictures of the P.S. 120 and 50 Humboldt polling stations, the one thing that the two have in common are the poll workers—nearly all of them veterans of many election days. They are the constants in a neighborhood undergoing rapid physical, social, and political change.

Although they would likely see far fewer voters at P.S. 120, Jamison and her team seemed unaffected by the dour projections for voter turnout. They arrived at five a.m. to set up the voting booths, dutifully manned the polls through a midday slump, and powered through the post-work rush from five to closing time at nine p.m.

They can’t control the 12 percent of voters who won’t walk through their doors, so they do their best to serve the declining numbers that do.

“We work as a family here,” Jamison said. “I won’t be here forever, but for now I like the work just fine.”

Leave a Reply